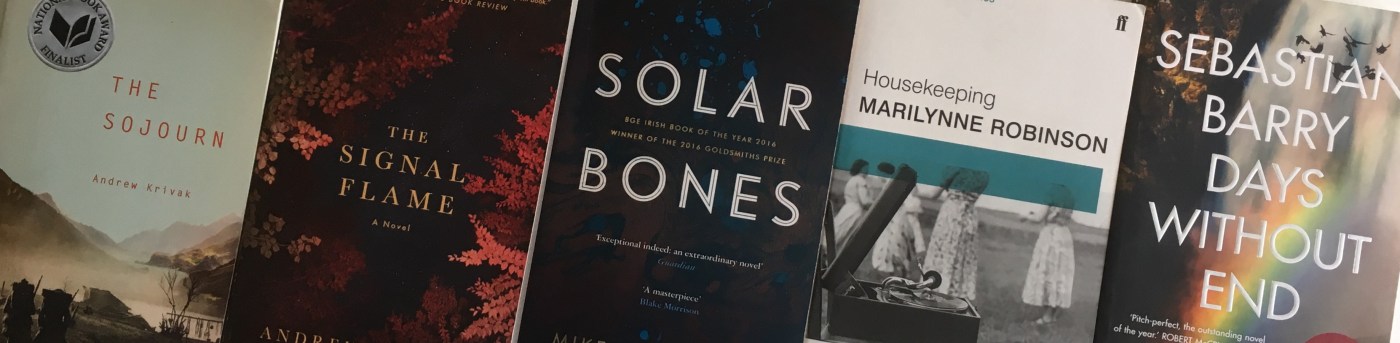

The subject of family has been a principle focus of fiction for centuries and yet our perceptions of the family unit is presently still changing. Below are five recommended reads which centre, either in part or wholly, upon the theme of family, with each of the novels listed below conveying familial unity or discord in an original and distinguished way. As you will read, each entry encompasses a unique point within history, from the American-Indian Wars of the 19th century to a modern-day Ireland still recovering from the economic collapse of 2008, and yet, regardless of the period, these authors have been drawn to portraying the individual lives of the fathers, mothers, sons and daughters of these tumultuous eras.

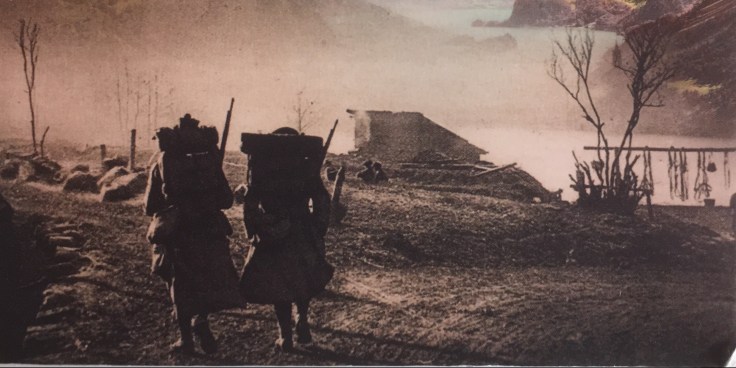

1. The Sojourn: Andrew Krivák (New York: Bellevue Literary Press, 2011)

The Sojourn, told through a reflective first-person account, documents the experiences of the Colorado-born Jozef Vinich, from his childhood as a shepherd, in Pastvina — a small rural community situated within the hinterlands of Hungary[1], alongside his father, Ondrej, and his orphaned cousin, Zlee — to his life as ‘an Austro-Hungarian conscript’[2], in World War One. Due to Vinich’s distinguished proficiency with a rifle, he is trained as a sharpshooter, or scharfschützen, in 1916, before being assigned to defend the Empire’s alpine regions, in 1917, from the advances of the Italian army upon the Empire’s ‘southern front’ (68). Whilst the novel is centred upon the survival of Vinich over the course of his life as a lance-corporal (68), ‘taught to hunt men’ (69), and his subsequent furtive peregrination homewards, to Pastvina, Krivák’s principle focus is that of the preservation of familial ties in the throes of war. Indeed, as the war progresses Vinich notes his single intention for his survival: to ‘see my father again’ (104).

Further to being paired with Zlee as one half of a renowned spotter and shooter unit for the majority of his service in the war, the subject of family permeates Vinich’s experiences: being both raised by Jozef’s father, Ondrej Vinich, the pair are united in their tutelage whilst working as shepherds of Ondrej’s flock and, therefore, assume a shared responsibility for protecting the family’s livestock. Ondrej’s training of the two adolescents in the skills of ‘shepherding and shooting’ (48) imbues within them a sense of discipline that is invaluable throughout their wartime deployments; in essence, within the Carpathian mountain range, their father shapes them (85). However, at its core, Krivák’s novel centres upon a self-exiled family, as all three men are in some capacity separate from their community and, at points, each other: Ondrej, due to his wife’s passing, in June 1899, and a hunting accident within the mountains of Dardan, Pennsylvania, in 1901, flees America in a state of remorse, and returns to his home-village of Pastvina, seeking a sense of atonement for his failings, and is an atonement that will never be achieved; Jozef, on the other hand, born in Pueblo, Colorado, is ‘a stranger’ (28) within his family’s homeland, and is a place in which he confesses to have ‘never belonged’ (190), living on the fringes of the ‘culture and land’ (28) known to his forefathers; whilst Ondrej’s ward, Marian, derogatively named Zlee by others, is an orphan and second-cousin to Jozef, having been abandoned by his mother, and who is denounced by the community as a ‘tough’ (47) following several violent exchanges in defence of others.

Despite this commonality, the Vinich family stoically endures the strains of loss and war. For Jozef, the family unit is preserved by him through recalling his memories of his past: remembering his father’s lessons within the Carpathians, conjuring his mother’s ‘shimmering’ (87) face whilst dreaming, and his recounting of his experiences alongside Zlee in the war. Krivák, through Jozef’s account of his war experiences, details the survival of a family when all around them the horrors of war are ever-present and devastating. Indeed, Krivák masterful work is equally a family chronicle as it is a war novel.

The Signal Flame: Andrew Krivák (New York: Scribner, 2017)

Andrew Krivák’s The Sojourn and The Signal Flame are entwined through their shared chronicling of the Vinich family, and there is an argument to be made that the novels should be counted as a single entry; however, each publication is another log within the telling of the Vinich family’s history, and so each entry should stand alone. Despite following Jozef Vinich’s descendants, this is a novel which inverses its predecessor’s narrative: centring upon the family awaiting the return of the son from war, as opposed to the son’s journey homeward. Beginning in 1972, and set within Dardan, Pennsylvania, the novel opens to the burial of Jozef Vinich, the patriarch of the family, who is survived by his daughter, Hannah, and her two sons, Bohumír ‘Bo’ Ondrej Konar, inheritor and now owner of his grandfather’s Endless Roughing Mill, and Samuel B Konar, a Corporal in the Unites States Army and currently MIA, last seen in ‘the province of Quang Tri’ (15). Indeed, each son comes to represent the opposing eras of their late grandfather’s life: Sam, the youngest, inherits his grandfather’s ‘gift’ (74) for marksmanship and his desire for active service, rising to the rank of ‘corporal’ (200) within the Marines, whilst Bo inherits control over the mill and his grandfather’s life’s work following his arrival within Dardan, in 1921; in summation, Jozef’s past and, prior to his death, his present, respectively. Evidently, the brothers commit themselves to two distinctly different paths through life, but paths that their grandfather had laid before them.

It is through Bohumír that Krivák charts the lives of three intertwining families: the Vinichs, the Konars and the Youngers as each family is, to some extent, shaped by the repercussions of war. For the Vinichs, Jozef, the narrator of Krivák’s preceding work, documented his survival as a sharpshooter in the Great War, stalking the mountain-ranges, alongside the indomitable Zlee, in defence of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in The Sojourn; for the Konars, the patronym assumed by Hannah Vinich following her marriage to Bexhet Konar, a veteran of the Second World War who is ‘broken’ (28) by his service, a note of cowardice is levelled at Bo and Sam’s beleaguered father due his flight from the battlefield, surviving the war in disgrace; and, finally, for the Youngers, the pregnant Ruth, the daughter of Bexhet Konar’s killer, Paul Younger, awaits the return of her fiancée, Sam Konar, from Vietnam. As each family processes the younger Konar’s disappearance, Bohumír is drawn to the past histories of these soldiers and their widows, and how, in the absences of these man, the family unit must persevere.

In order to appreciate the scale of Krivák’s expansive scope, the novels should be read and enjoyed in succession. Krivák, in his documenting of the familial ties shared between each collective, has produced a tale of endurance, as each family explores their own capacity for accepting both their circumstances and, in the process, their acceptance of one another. As Hannah and Bohumír are frequently drawn to recalling their memories of the deceased Jozef and the missing Sam, Krivák documents a family’s hard-fought rise from grief to a state of acceptance, with the family steering themselves forward into an uncertain future without either their patriarch or one of their scions. With their attempt at formulating a new status-quo, the Konars harbour their losses together, as the repercussions of war test the resilience of a family and their steadfast unity.

3. Solar Bones: Mike McCormack (Edinburgh: Canongate, 2017)

From the first sounding of the Angelus bell, the spectral Marcus Conway, a county-engineer from the outskirts of the village of Louisburgh, County Mayo, finds himself in his kitchen with little more than two newspapers, one a local paper and the other a national-press release, and the unchronological recollections of his entire history. In one single, unbroken sentence, Conway candidly reveals his past and discloses his outlook upon his life’s achievements and his management of its challenges: discussing Ireland’s banking collapse; his childhood interest in engineering; his role as a husband and a father; his reaction to his daughter’s experimental art career; his care for his wife following her contraction of a virus from the county’s contaminated water-supply; his professionalism in light of political pressures; his morality following an affair; his opinion upon his son’s life of travel; his father’s descent into dementia; and, finally, his last day. Like Conway himself, McCormack’s sequencing and structuring of the novel is out of time, and yet this revenant’s (229) retelling of his own history is grounded by his intermittent return to his duties, familial or otherwise, as a ‘man and boy, father and son, husband and engineer’ (262).

It is in his service to these responsibilities that Conway explores his own history: in his present state upon the cusp of infinity, by being tethered to his family’s history he may examine, through hindsight, his life’s successes and his failings. In essence, McCormack’s novel is a series of vignettes told by a ghost as means to understand what it takes to be human. Conway’s dissection of the quotidian features of life was, prior to the novel’s publication by Tramp Press, dismissed by prospective publishing houses due to the ‘domesticity’[3] of the novel’s focus. However, it is due to McCormack’s attention to a single man’s life that he has, as noted by Justine Jordan in her interview with the author for The Guardian, created a character as ‘not one of his usual outcasts and oddballs, but a character with “complete involvement with the world”[4]. Recently, since the novel’s publication, McCormack has claimed the 2016 Goldsmith’s Award, the 2016 Irish Book Awards and the 2017 International Dublin Literary Award, and further attests to the point that readers, like McCormack during his seven year process of writing the novel, will keep ‘going back’[5] to Conway’s single-sentence soliloquy on being a ‘father, husband, [and] citizen’ (265) for years to come.

4. Housekeeping: Marilynne Robinson (London: Faber & Faber, 2015) (First published in 1980)

In Marilynne Robinson’s first novel, Housekeeping, the subject of transience is central to the lives of sisters Ruthie and Lucille Foster; throughout, the pair, abandoned by their mother and wards to a string of family members, must lead lives void of structure in the town of Fingerbone, in Idaho, a place noted for its ‘religious zeal’ (182) and attention to ‘social graces’ (183). Through Ruthie’s omniscient first-person narration, Robinson documents the lives of two young-women as they are passed from one relative to the next with the impending threat of wardship of the state underlining their family life. Within the novel’s opening lines, the sisters’ shared existence is noted in Robinson’s clipped prose:

My name is Ruth. I grew up with my younger sister, Lucille, under the care of my grandmother, Mrs. Sylvia Foster, and when she died, of her sisters-in-law, Misses Lily and Nona Foster, and when they fled, of her daughter, Mrs. Sylvia Fisher. Through all these generations of elders we lived in one house, my grand-mother’s house, built for her by her husband, Edmund Foster, an employee of the railroad, who escaped this world years before I entered it. It was he who put us down in this unlikely place. (Emphasis added)

As is noted, the family do not leave Fingerbone as much as they escape its boundaries. In both emphasised instances, the girls have not been left but rather abandoned by their ageing relatives and it is from this brief passage alone, Robinson’s attention to the Fosters family’s leaving of Fingerbone, either through choice or through death, presents the simple central question facing the sisters: can they remain together as family? Beyond the issue of the sisters’ care, both Ruthie and Lucille must contend with life within Fingerbone, from finding societal constraints forced upon them to enduring the natural calamities that befall the town. It is with Mrs. Sylvia Foster, the sisters’ idiosyncratic aunt, that the family are at once united and divided, as Ruthie’s affinity for her mother’s sister is countered by Lucille’s wish to escape Fingerbone itself: in essence, Ruthie must either gain a guardian or lose a sister. Robinson’s debut novel, first published in 1980, does not only stand as a prelude to her renowned Gilead Trilogy, a series involving, both centrally and peripherally, the Reverend John Ames, and set within the series’ titular town, but also as an intimate examination of family life within a small, rural Midwestern town of America.

5. Days Without End: Sebastian Barry (London: Faber & Faber, 2016)

Sebastian Barry’s latest novel, Days Without End, follows the recollections of Thomas McNulty, an Irish immigrant from Sligo, as he documents his life in America, following his arrival in Quebec, Canada. Escaping from starvation only to enter into a life of ‘soldiering’ the violence of the Indian Wars and then, later, the American Civil War, McNulty endures the formative years of America’s western frontier and the preservation of the Union, respectively, alongside his ‘brother-in-arms’ and love, John Cole. Barry’s literature is, when viewed holistically, a chronicle of two families[6]: the McNultys and the Dunnes. Barry’s oeuvre is drawn to the two clans across 19th and 20th centuries: looking exclusively at Barry’s novels — the Dublin writer is both a novelist and a playwright — three works centre upon the Dunne family — Annie Dunne (2002), A Long Long Way (2005), and On Canaan’s Side (2011) — and four upon the McNultys — The Whereabouts of Eneas McNulty (1998), The Secret Scripture (2008), The Temporary Gentleman (2014) and Days Without End (2016)[7]. With his focus centred upon the exploration of these two collectives, Barry explores the fractured histories of both families; in defining the sprawling, branching lives of these family trees, Barry searches for the individual within the unrecorded moments of the past, and so produces, through the protagonist of each novel, a log, or vignette, of a period within the timeline of these people, from inaccurate word of mouth rumours to the compromised first-hand accounts from the individuals in question. It is through the latter, therefore, that Barry creates the journeyman that is Thomas McNulty.

In the wake of McNulty’s meeting with John Cole ‘under hedge in goddamn Missouri’ (3) due to a storm, the two men embark upon an odyssey beginning with their ‘dancing days’ (4), in Daggsville, as close friends before creating, fifteen years later, their own family unit: with McNulty and Cole adopting an orphaned Sioux Indian child, Winona, as their daughter, following the slaughter of the child’s tribe upon the plains of Wyoming by the pair’s regiment. It is from this lawless frontier that McNulty and his ‘beau’ (197), Cole, must persevere and endure the hardships of life as soldiers, wanderers, lovers and fathers. However, this hostile landscape is beautifully realised through McNulty’s retelling of his youth, his ‘days without end’, and reads like, as Barry has noted, an ‘eyewitness account’[8] from the point-of-view of the protagonist himself. It is chronologically told from an undetermined point within McNulty’s life, and Barry’s prose reflects the syntax of a man whose language was formulated gradually through his travels. At the heart of McNulty’s retelling of his life, his priority is revealed: ‘to keep Winona safe’ (248). His transient existence, alongside Cole, is wishfully anchored and, hopefully, forever tethered to the homestead through the adoption of Winona, as all three survivors of the American planes are united by their love for one another in the wake of the savagery that McNulty and Cole have enacted and rejected.

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/27/books/review/signal-flame-andrew-krivak.html

[2] https://www.andrewkrivak.com/book/

[3] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4EM6VIHjhzI&t=411s

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/books/2017/jun/24/mike-mccormack-soundtrack-novel-death-metal-novel-solar-bones

[5] Ibid.

[6] https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/oct/28/days-without-end-by-sebastian-barry-review

[7] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/03/books/review/days-without-end-sebastian-barry.html: Smith’s point of the novel being the fourth in a series was similar to my note.

[8] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WV0m2kux-2A

Leave a comment