The Long Take, or A Way to Lose More Slowly

Robin Robertson’s first foray into the novel form is a blistering account of one man’s itinerant journeys throughout post-war America, from 1946 to 1953. The novel’s speaker is the wandering Walker, a veteran of The North Novas, whose harrowing experiences within ‘Normandy, then Belgium, Holland’ have left an unbreakable tether to his past service. While initially sojourning the dive-bars and a cheap one-room ‘walk-up’ of New York, Walker, as his ‘name and nature’ attests to, sets off for another coastline, hitchhiking to Los Angeles where he settles as a writer for The Press’s city desk.

In Walker, Robertson has found a true journeyman: navigating the opposing coasts of a post-war America as both a veteran seeking an escape from his past and a writer seeking to find the narratives of his forgotten servicemen. Walker’s listless meanderings are given direction by a single cause: to report upon the plight of homeless veterans along the west coast. It is a simple endeavour assigned to him, upon request, by The Press. Helped by the spectral-like Billy Idaho, a veteran of the ‘4th Infantry’, who has, since his return to Los Angeles, become something of an authority upon Skid Row, Walker begins his endeavour.

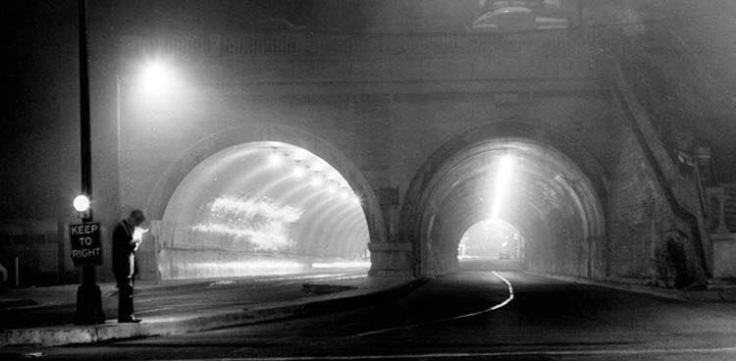

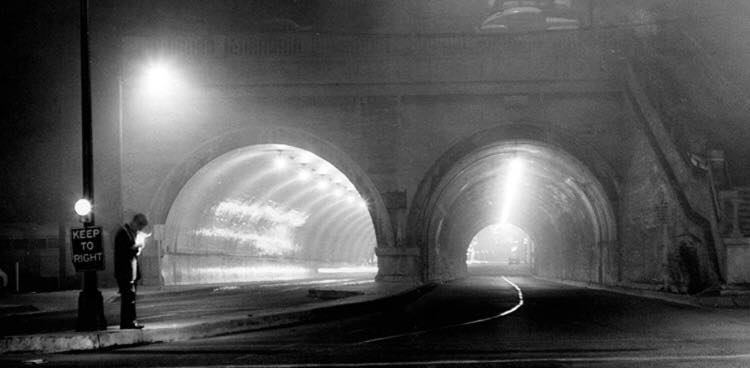

The America of the narrative, however, is a confluence of new developments and stagnation, with the imposing demolition forces hunting any trace of bygone eras, typically at the cost of displacing the impoverished denizens of a city’s low-income housing. As Walker identifies the locations of the film-sets of Los Angeles, cinema becomes more of a record or document of the city’s past, rather than a form of interest or escape for Walker: as he navigates the streets, he may note an ‘inventory of loss’ as the city is filleted and carved for the ‘freeways’ and ‘parking lots’. Celluloid, here, serves as a means to archive the city’s ever-changing landscape. With this constant destruction and rebuilding of the city, Walker cannot help but sense that Los Angeles is being savaged by a ‘four-ton wrecking bell’ opening any building within its path: in essence, through the ‘fog and smoke’, the city becomes yet another battlefield for those soldier of World War Two and the Korean War.

Robertson’s amalgam of verse and prose conveys Walker’s hardships in visceral detail. Each vignette, past or present, is a single scene of Walker’s life, and is read more like a series of snap-shots, fleeting instances, rather than a single narrative thread. This fracturing perfectly reflects the mindscape of Walker, as, like him, the reader is never too far away from the past:

We walked down the choir of the forest carrying the dried-up stalks and pods of bluebells–our summer rattles–on through the opened trees: our ceremonies of light in the green cathedrals.

*

These moons in their hundreds, pinked underneath by the beginnings of daylight, are barrage balloons towed by the boats. Seven thousand in this dawn armada. Ships and the wakes of ships. As if a giant was drawing them on strings, out from the harbor. The Channel so thick with traffic you could cross it on the backs of boats.

*

He’d sleep out on the roof, these nights,

and stare at this city

that’s too big to measure,

has too many windows to watch.

And nobody sees or cares anyway,

so nothing matters.

There’s no more room in this high city: all human scale is lost.

While alternating between verse and prose, Robertson also intermittently transitions from a subjective third person narration to a first-hand account, either through memory or through occasional diary entries, Walker is laid bare: his thoughts and perceptions left undisclosed for the reader. Over the span of twelve lines, Robertson has returned to a fleeting instance of Walker recounting a peaceful moment he shared with Annie McLeod, his past-love, before then distilling an image from Walker’s memory of travelling to war and only to then bring Walker back to his present predicament: sleeping atop a roof away from the hustle of the New York streets. However, these silent moments of introspection are often counterbalanced with sudden jolts of violence, as though clipped from the pages of coal-black noir that Robertson has mined:

The fear of corridors, elevators, attics, cellars,

windows, doors. Staircases, most of all.

Wading through shadows, black pools,

then a long wedge of light

swinging open at an angle like a curtain

slashed by a knife. The floor tips

and drops away, and the door closes. Ink dark.

White rods slide out of the wall, razor-edged

by shadow, beginning to splay

and take in everything, then

snapping shut. Light locked

in a dark room. This whole city is a trap.

*

‘You one of them Reds? One of them infil-traitors?

Sitting there with your book, listening in.’

Walker looked up from his seat in the corner.

‘Yeah. I’m talking to you, Mac. You a Commie?’

‘Hey, give the guy a break. He’s a regular.’

‘What’s he reading, anyway? Look–I told ya!

Red Harvest, it’s called! That proves it.’ ‘Leave it, Joe.

He’s not bothering anyone.’

‘Joe?’ Walker smiled. ‘Joe Stalin ?’

He caught the swinging fist and pushed it down

onto the table, onto his empty shot-glass–

watching the table fill, and Uncle Joe turn gray.

As is shown within the excepted first verse, the light’s glare is akin to a blade: at once, the light is a ‘wedge’ capable of ‘snapping shut’ like a switchblade; light swings ‘open at an angle like a curtain slashed by a knife’; and shadows are ‘razor-edged’. For Walker, each cityscape is equally a source of refuge as it is an opponent capable of harming, even killing, its occupants. Beyond the hostility of the cities themselves, Walker, as he roams the streets, must contend with the volatility of their inhabitants. Here, the colloquial dialogue exchanged between Walker and Joe is, at once, quotidian to and expected from the string of dive-bars Walker frequents and is also characteristic of the pages of Dashiell Hammet oeuvre. Like Hammet’s famous taciturn narrator, the Continental Op, and the string of hardboiled detectives which stalked through the dark recesses of Los Angeles in his wake, Walker’s strength lies in his handling of others: the manner of his fight with Joe is trimmed to two verbs ‘caught’ and ‘pushed’ and yet, despite the sparsity of the verse, Robertson vividly distils the brutality of the exchange. Like the noir isolates that have preceded him, Walker is often provoked to violence by those who misunderstand their adversary.

Having claimed both the Goldsmiths Prize and the Roehampton Poetry Prize, The Long Take, or A Way to Lose More Slowly is a force of both poetry and prose. Robertson’s hybrid-novel is a work of fiction that is an examination of homelessness and society’s treatment of outsiders. In his review of the novel for The Guardian, John Banville labelled Walker ‘a wonderful invention, a decent man carrying the canker of a past sin for which he cannot forgive himself’[1]; it is an analysis that reaches the centre of the novel: Robertson has centred his narrative, and his narrator’s journeys, upon the past’s durability in the face of an altering present.

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/mar/24/long-take-robin-robertson-poetry-review

Leave a comment