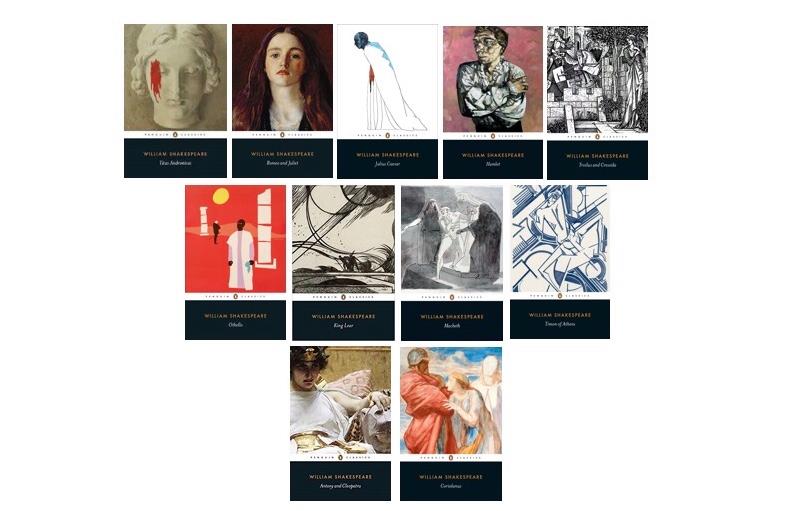

Of the thirty-seven plays attributed to William Shakespeare, eleven have been identified as his ‘tragedies’. Typically with these works, and while an amalgam of multiple genres and tropes, Shakespeare centres these eleven narratives upon an ambitious, often self-reflective, protagonist who is beset with an unavoidable fault or an overpowering hamartia. Their course is plagued by ‘saucy doubts and fears’ which, by each plays’ denouement, results in the individual’s sacrifice and doom. This list is one still debated by scholars and is by no means a definitive selection, but I have followed the plays typically seen as Shakespeare’s ‘Tragedies’.

Shakespeare’s Tragedies: 01/11

Titus Andronicus (1591-1593) After his defeat of the Goths, the titular general returns to Rome and is bequeathed the title of Emperor. In his homecoming, Andronicus does not return empty-handed; accompanying his is the Queen of the Goths (Tamora), her three sons (Alarbus, Chiron, and Demetrius), and Aaron the Moor (her secret lover). What follows is an unflinching tale of revenge, which is fallen in and out of the public’s favour since its release.

TITUS ANDRONICUS

Hail, Rome, victorious in thy mourning weeds!

Lo, as the bark, that hath discharged her fraught,

Returns with precious jading to the bay

From whence at first she weigh’d her anchorage,

Cometh Andronicus, bound with laurel boughs,

To re-salute his country with his tears,

Tears of true joy for his return to Rome.

Shakespeare’s Tragedies: 02/11

Romeo & Juliet (1594-1595)

Within the peaceable streets of Verona, the ancient mutiny between two noble houses, the Montagues and the Capulets, continues through the skirmishes of their families’ servingmen. Before long, the two Houses have freshly renewed their violent history in pursuit of attaining bitter reprisals and protecting what remains of their blackened honours; all the while, the fates of two star-crossed lovers, divided by their antecedents hatred but united in their forbidden love, become tragically intertwined.

A single Italian tale, through the form of two texts – The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet by Arthur Brooke, published in 1562, and retold in prose in Palace of Pleasure by William Painter, in 1567 – served as the source of Shakespeare’s play. Written between 1594-1595, and published in 1597, the influence of the Tragedy of Romeo and Juliet upon literature is immeasurable.

JULIET

‘Tis but thy name that is my enemy;

Thou art thyself, though not a Montague.

What’s Montague? it is nor hand, nor foot,

Nor arm, nor face, nor any other part

Belonging to a man. O, be some other name!

What’s in a name? that which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet;

So Romeo would, were he not Romeo call’d,

Retain that dear perfection which he owes

Without that title. Romeo, doff thy name,

And for that name which is no part of thee

Take all myself.

Shakespeare’s Tragedies: 03/11

Julius Caesar (1599-1600)

Who was Julius Caesar? Demagogue or tactician? Traitor or patriot? Aggressor or peacekeeper? Emperor or king? It is the last of these questions that plays upon the shrewd mind of Marcus Junius Brutus. It is a concern that, with the aid of Cassio’s – his brother in-law’s – persuasion, a fellow senator and so-called ‘liberator’, motivates the once loyal Brutus to betray his trusting emperor, a man who may have also been, it was believed, Brutus’s biological father. The Liberators’ betrayal of Caesar ignites a vicious civil war and plunges Roman against Roman in a brutal struggle for rule and supremacy.

Shakespeare’s account of the events preceding and succeeding the 15 March 44 BC distill individuals, war-jaded all, from a world-altering event, finding the personal through the Liberators and their pursuers’s vows of peace and revenge, respectively.

Within this unrelenting study of the collapse of one man’s morality against the backdrop of political upheaval, Shakespeare examines the frail tethers that bind betrayal and friendship, beliefs and politics, and fact and fiction. These subjects are enemies, but their battle takes place within one: Brutus, Caesar’s most trusted advisor.

BRUTUS

It must be by his death: and for my part,

I know no personal cause to spurn at him,

But for the general. He would be crown’d:

How that might change his nature, there’s the question.

It is the bright day that brings forth the adder;

And that craves wary walking. Crown him?–that;–

And then, I grant, we put a sting in him,

That at his will he may do danger with,

The abuse of greatness is, when it disjoins

Remorse from power: and, to speak truth of Caesar,

I have not known when his affections sway’d

More than his reason.

Shakespeare’s Tragedies: 04/11

Hamlet (1600-1601)

Adapted by Shakespeare, in 1601, from the legend of Amleth, as chronicled by the Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus, and then translated by 16th-century scholar François de Belleforest, Hamlet has become the quintessential epitome of the tragic figure: determined to succeed but bound to fail.

Within the hours of twilight, Hamlet is charged by the spirit of his late father, the King of Denmark, to avenge his murder – assassinated within his orchard by the ‘serpent’ of a brother, Claudius, no less. The newly crowned King, purportedly guilty of the entwined acts of regicide and fratricide, has taken Hamlet’s mother, Gertrude, as his queen; therefore adding incest to Claudius’s treason.

Subsequently, Hamlet vows to avenge his father and so rallies against the royal family of Denmark, but does so with caution and vigilance. Feigning madness, Hamlet wishes to draw a confession from Claudius before committing the same act that has fanned his manipulative uncle. Facing Hamlet is Polonius, the stalwart advisor to the King and erudite tactician who attempts to investigate the aloof Prince and his schemes.

Drawn to melancholia and doubt, Hamlet’s self reflection makes him not only Shakespeare’s most introspective protagonist, but also his most profoundly human:

HAMLET

Now I am alone.

Oh, what a rogue and peasant slave am I!

Is it not monstrous that this player here,

But in a fiction, in a dream of passion,

Could force his soul so to his own conceit

That from her working all his visage wanned,

Tears in his eyes, distraction in his aspect,

A broken voice, and his whole function suiting

With forms to his conceit? And all for nothing—

For Hecuba!

What’s Hecuba to him or he to Hecuba

That he should weep for her? What would he do

Had he the motive and the cue for passion

That I have? He would drown the stage with tears

And cleave the general ear with horrid speech,

Make mad the guilty and appall the free.

Shakespeare’s Tragedies: 05/11

Troilus and Cressida (1602)

Bracketed by Frederick S. Boas as one of Shakespeare’s three ‘Problem Plays’, Troilus and Cressida, in contrast to the playwright’s previous foray into history, is drawn from Greek mythology and centres upon the denouement of the Trojan War, retelling events of Homer’s The Iliad.

The narrative is split: while the burgeoning love between titular pair is foregrounded within the narrative, Shakespeare presents the political intrigue of the warring forces of the invading Greeks and the stalwart Trojans, as the war-councils of Kings Agamemnon and Priam, respectively, are the principle engagements of the narrative.

Tonally, the intermittent shifts from comedic slights to visceral violence place the play as an anomaly, hence the categorising as a ‘Problem’. In a move away from Roman history, Shakespeare’s retelling is Greek mythology continues in the footsteps of the ancient writers who preceding him.

PROLOGUE

In Troy, there lies the scene. From isles of Greece

The princes orgulous, their high blood chafed,

Have to the port of Athens sent their ships,

Fraught with the ministers and instruments

Of cruel war: sixty and nine, that wore

Their crownets regal, from the Athenian bay

Put forth toward Phrygia; and their vow is made

To ransack Troy, within whose strong immures

The ravish’d Helen, Menelaus’ queen,

With wanton Paris sleeps; and that’s the quarrel.

To Tenedos they come;

And the deep-drawing barks do there disgorge

Their warlike fraughtage: now on Dardan plains

The fresh and yet unbruised Greeks do pitch

Their brave pavilions: Priam’s six-gated city,

Dardan, and Tymbria, Helias, Chetas, Troien,

And Antenorides, with massy staples

And corresponsive and fulfilling bolts,

Sperr up the sons of Troy.

Shakespeare’s Tragedies: 06/11

Othello (1603)

Of all of Shakespeare’s protagonists, the Moorish general Othello is unquestionably the playwright’s most noble, and Iago, the general’s ensign, the most corrupted. As a general of the Venetian army, Othello’s military prowess is renowned throughout Venice, revered as an ‘honourable lieutenant’. His ensign’s reputation as an ‘honest man’, however, could not be further from the truth.

Beholden to Desdemona, his new bride, Othello is blinded by his enduring adoration, and does not see the thread by which Iago schemes his commander’s unspooling. Iago’s treachery is one which is enacted with a simplicity that reduces the honourable Othello to a raging beast; the tragic plot commences by the placement of a simple possession: Desdemona’s handkerchief. Seeing his general’s infatuation, Iago unseams the couple’s unity by calling into question the friendship between Desdemona and the lieutenant Cassio. With Iago, an innocent friendship may be distorted into furtive love.

A play which portrays the dangers and consequences of untempered anger and of unfounded hearsay, respectively, Othello follows a man’s descent into jealousy, and another man’s revelry at his doing:

IAGO

Thus do I ever make my fool my purse:

For I mine own gain’d knowledge should profane,

If I would time expend with such a snipe.

But for my sport and profit. I hate the Moor:

And it is thought abroad, that ‘twixt my sheets

He has done my office: I know not if’t be true;

But I, for mere suspicion in that kind,

Will do as if for surety. He holds me well;

The better shall my purpose work on him.

Cassio’s a proper man: let me see now:

To get his place and to plume up my will

In double knavery—How, how? Let’s see:—

After some time, to abuse Othello’s ear

That he is too familiar with his wife.

He hath a person and a smooth dispose

To be suspected, framed to make women false.

The Moor is of a free and open nature,

That thinks men honest that but seem to be so,

And will as tenderly be led by the nose

As asses are.

I have’t. It is engender’d. Hell and night

Must bring this monstrous birth to the world’s light.

Shakespeare’s Tragedies: 07/11

King Lear (1605)

The lengthy reign of King Lear has left the ailing monarch exhausted and desiring to relinquish his duties to his court and realm. Prior to his intended abdication, Lear brings forth a proposition of entitlement to his three daughters- Goneril, Regan and Cordelia: if one of the sisters can convince their father of her absolute love, then she will be his sole heir. While the obsequious and servile ploys of Goneril and Regan, – encouraged by their husbands the Duke of Albany and the Duke of Cornwall, respectively – are lapped up by their conceited father, Cordelia does not entertain such vanity. It is an act of defiance that will send the family into dislocation and ruin, and will result in Cordelia’s exile and disinheritance.

What follows is a tale warning of the dangers of pride and egomania, and how the intrigue of the courts and the lure of power may corrupt.

KING LEAR

Meantime we shall express our darker purpose.

Give me the map there. Know that we have divided

In three our kingdom: and ’tis our fast intent

To shake all cares and business from our age;

Conferring them on younger strengths, while we

Unburthen’d crawl toward death. Our son of Cornwall,

And you, our no less loving son of Albany,

We have this hour a constant will to publish

Our daughters’ several dowers, that future strife

May be prevented now. The princes, France and Burgundy,

Great rivals in our youngest daughter’s love,

Long in our court have made their amorous sojourn,

And here are to be answer’d. Tell me, my daughters,–

Since now we will divest us both of rule,

Interest of territory, cares of state,–

Which of you shall we say doth love us most?

That we our largest bounty may extend

Where nature doth with merit challenge. Goneril,

Our eldest-born, speak first.

Shakespeare’s Tragedies: 08/11

Macbeth (1606)

Following the successful expulsion of the invading Irish-Norwegian forces from the Scottish realm, King Duncan, the ‘great’ monarch, bequeaths his most ‘valiant’ and ‘worthy’ general, Macbeth, the Thane of Glamis, a new title: that of the Thane of Cawdor, awarding Macbeth with the position once held by a traitor and conspirator against the crown and court. While an honour, and soon to be a notable instance of irony, the appellation serves, more importantly, as confirmation of a prophecy previously disclosed to the thane and his ‘noble’ confidant, Banquo, by ‘three weird sisters’, with their predictions culminating in Macbeth assuming the highest office of the realm.

With his wife as a calculating and ruthless accomplice, Macbeth sets to enacting the witches’ prophecies, regardless of the unshakeable toll borne by his soul. In the usurpation of the ethereal and angelic King Duncan, the Macbeths install themselves as the tyrannical rulers of a maligned and unstable kingdom: the nobility, once the trusted advisors of the monarchy, are now prey to their king and the eventual adversaries.

Shakespeare’s revisions to Holinshed’s Chronicles, the source of the play, were made in order to elide the treachery of Banquo, who, at the time of Shakespeare’s composition of the play, was believed to be distantly related to King James I, the principle audience of the bard’s tragedy, with monarch having assumed he throne three years earlier.

Now seen as ‘the’ GCSE play, Macbeth still remains a fierce and visceral drama which serves as a lesson of the dangers of unchecked ambition and totalitarian control.

MACBETH

We have scotch’d the snake, not kill’d it:

She’ll close and be herself, whilst our poor malice

Remains in danger of her former tooth.

But let the frame of things disjoint, both the

worlds suffer,

Ere we will eat our meal in fear and sleep

In the affliction of these terrible dreams

That shake us nightly: better be with the dead,

Whom we, to gain our peace, have sent to peace,

Than on the torture of the mind to lie

In restless ecstasy.

Shakespeare’s Tragedies: 09/11

Timon of Athens (1606)

Critically viewed as one of Shakespeare’s ‘problem plays’, Timon of Athens charts the downfall of the once kind and generous titular Athenian lord into a spiteful misanthrope, mourning the equal loss of his status and his fortune.

Despite the work being eclipsed by the tragedies both preceding and succeeding it, Timon of Athens still remains a cautionary tale of the perils of greed and bitterness.

PAINTER

Look, more!

POET

You see this confluence, this great flood

of visitors.

I have, in this rough work, shaped out a man,

Whom this beneath world doth embrace and hug

With amplest entertainment: my free drift

Halts not particularly, but moves itself

In a wide sea of wax: no levell’d malice

Infects one comma in the course I hold;

But flies an eagle flight, bold and forth on,

Leaving no tract behind.

PAINTER

How shall I understand you?

Shakespeare’s Tragedies: 10/11

Antony & Cleopatra (1607)

Charting the fateful fall of the titular couple from Pompey’s Sicilian revolt, in 44 B.C, to the Egyptian Queen’s suicide, detained by Octavius Caesar, in 30 B.C, Shakespeare’s second Roman play follows the lives of the warring leaders of Rome’s Second Triumvirate.

Here, while having achieved a united front against the assassins of the empire’s erstwhile dictator, Julius Caesar, the Second Triumvirate- Octavius Caesar, Marc Antony and Marcus Lepidus – are now each embittered and blighted by their contempt for one another. Without the joint pursuit of avenging their slain leader, the collective search for ways to triumph over each other.

Beguiling Antony, however, is the Queen of Egypt, Cleopatra. Throughout, Egypt’s reigning monarch is portrayed as a calculated tactician, astute and prudent to the political forces baying at her kingdom’s borders. Opposing her stands Octavian Caesar, a ruthless and skilful strategist who is now, with the murder of his great-uncle, the natural heir to Rome’s ever-expanding empire. In time, the might of Octavius far exceeds that of the tempestuous tragic lovers.

With Antony & Cleopatra, Shakespeare’s study of the political intrigue of Rome’s transition from the dictatorship of Julius Caesar to the ascension of the Empire’s first emperor, Augustus.

PHILO

Nay, but this dotage of our general’s

O’erflows the measure: those his goodly eyes,

That o’er the files and musters of the war

Have glow’d like plated Mars, now bend, now turn,

The office and devotion of their view

Upon a tawny front: his captain’s heart,

Which in the scuffles of great fights hath burst

The buckles on his breast, reneges all temper,

And is become the bellows and the fan

To cool a gipsy’s lust.

Shakespeare’s Tragedies: 11/11

Coriolanus (1605-1608)

Gaius Marcius is a peerless Roman general, committed to the protection of Rome; Marcius , in the wake of the exiling of the final Tarquininan King, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, is now faced with a plebeian revolt: the grain shortage within the capital is at crisis point, and is attributed to the will of the patricians- Rome’s ruining class. It is here that Coriolanus’s diplomacy is shown to be lacking: he is not tactful nor is he sympathetic to the masses, and he instead scolds them, threatening to ‘make a quarry/With thousands of these quarter’d slaves’. Indeed, Marcius believes that his sword is not only useful upon a battlefield.

Following the Roman Army’s siege of the town of Corioli, expelling the Volscian people and their military leader, Tullus Aufidius, Marcius is heralded by his peers and is bequeathed the titular cognomen of Coriolanus.

At the behest of his mother, Volumnia, Coriolanus enters Roman politics, with the support of the senate and, seemingly, the people. However, the manipulations of the senate leave Coriolanus riled and enraged. In a scathing outburst, Coriolanus finds the senate’s adherence to the people’s voices a debasement of their ‘seats’ and rallies against the republic’s democracy.

Exiled, Coriolanus charts a course of revenge, seeking out the enemies of Rome to make them his allies. Shakespeare’s final tragedy is one replete with the political intrigue of his preceding Roman plays and yet is charged with the violence of Macbeth. Coriolanus is a brutal denouement of Shakespeare’s tragic oeuvre.

CORIOLANUS

‘Shall’!

O good but most unwise patricians! why,

You grave but reckless senators, have you thus

Given Hydra here to choose an officer,

That with his peremptory ‘shall,’ being but

The horn and noise o’ the monster’s, wants not spirit

To say he’ll turn your current in a ditch,

And make your channel his? If he have power

Then vail your ignorance; if none, awake

Your dangerous lenity.

Leave a comment