No Country for Old Men [2005], Cormac McCarthy’s ninth novel, follows the concluding volume of The Border Trilogy, Cities of the Plain, with a break from the ‘cowboys and horsemen’[1] of the American West and into a post-Vietnam Texas altered by war. Along with the relocation of the narrative’s period, McCarthy drastically revises the functions behind the individual’s travel; for instance, in The Crossing, each of Parham’s three journeys into Mexico have a deliberate objective: from his initial travel as the ‘custodian’[2] of the trapped wolf, to his attempts at reclaiming the family’s stolen horses, before his concluding journey to ‘find his brother’ (673), all display a clear intention that is initially dictated by the individual. In No Country for Old Men, on the other hand, travel is the outcome of either one of two objectives: pursuit or escape. The Coens, in their faithful adaption of McCarthy’s novel, convey the determination of the pursuers and the subsequent desperation of the pursued.

In comparison to the functions of travel throughout McCarthy’s earlier Western works, specifically those of The Border Trilogy, in which travel is, initially, dictated by the individual, No Country for Old Men shows Moss, Bell, and Chigurh journeying in order to, either, elude or pursue another. For instance, alongside the Kid of Blood Meridian, who leaves the homestead in a wilful act of separation, John Grady Cole and Lacey Rawlins travel into Mexico in order ‘to work’[3]. In All the Pretty Horses, McCarthy emphasises the pair’s journey as being one purely of choice, as stated ‘we just left. We didn’t have to’[4]. This stress upon the individual’s desire to travel is shown throughout the next two instalments of The Border Trilogy, specifically in Parham’s three journeys into Mexico, during The Crossing; which are, to an extent, as stated by Arnold, in aid of ‘his [Parham’s] youthful, and romantic desires’[5]. In No Country for Old Men, however, McCarthy replaces Parham’s ‘youthful […] desires’ with the harsh, unrelenting realities of violence.

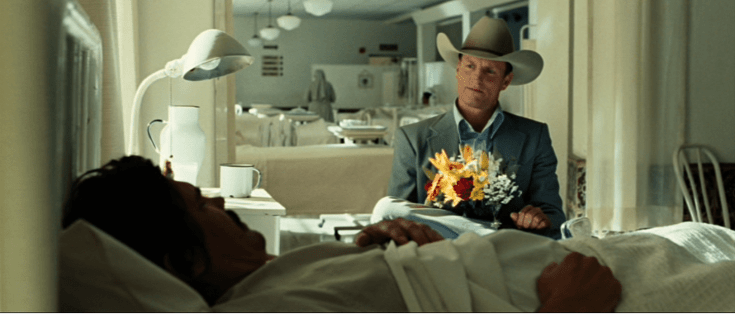

The travel of Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), for instance, is propelled by escape, by an attempt to avoid ‘the sorts […] that are huntin him’[6], following the theft of a satchel, containing ‘two point four million’ (23) dollars, from the aftermath of a drug transaction. In relation, and in contrast, to Moss’s escape is the function of Anton Chigurh’s (Javier Bardem) travel, enacting a dogged pursuit of, both, the satchel and Moss himself. Finally, Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones) holds a liminal standpoint within the wake of the conflict, and provides, through his investigation, the act of pursuit; however, alongside this, with his ultimate retirement from the authorities, Bell enacts his own form of escape: unable and unwilling to, as proposed by Kenneth Lincoln, ‘pursue the pure evil of Anton Chigurh’[7] any longer.

Moss’s travel is reduced to a single point of chance, as defined during Carson Wells’s reflection; in which, he outlines the former’s position following the opening crime scene, as stated ‘you just happened to find the vehicles out there’ (151). McCarthy removes the initial control over the individual’s travel, as seen throughout The Border Trilogy, with Moss’s discovery. Indeed, a convincing argument can be made that Moss’s theft of the satchel is an act of freewill, and, to a degree, it is. Moss’s travel, however, does not commence due to the taking of the satchel, but rather from the threat of pursuit, incarceration, or death following his return to the scene, and the tracker’s inevitable use of the details from his abandoned vehicle, as stated:

He was thinking about his truck. When the courthouse opened at nine o’clock Monday morning someone was going to be calling in the vehicle number and getting his name and address. […] By then they would know who he was and they would never stop looking for him. Never, as in never. [36]

Indeed, Moss comprehends the possible dangers immediately after taking the satchel, outlining that ‘beyond all this was the dead certainty that someone was going to come looking for the money’ (18-19). However, it is only with his return to the scene, an act stemming from the guilt of leaving a dying man without water, or ‘agua’ (12), as stated ‘are you dead out there? […] Hell no, you aint dead.’(23), that any form of connection is tied to Moss. Here, through his actions, the threat of violence becomes a reality: following his return, Moss is subsequently compelled to travel, and it is from this point onwards that his journey is driven by escape. With the objectives explored during No Country for Old Men, McCarthy replaces the earlier texts’ idealism, found at the beginning of Grady and Parham’s journeys in The Border Trilogy, with the individual’s attempts to either elude or enact violence by means of travel. Indeed, in the Coens’ adaption, McCarthy’s internal subjective narration is understandably omitted. In place, Moss, verbatim, delineates to his unassuming wife, Carla-Jean Moss (Kelly Macdonald) his concern, ‘look, right now it’s midnight Sunday. The court house opens nine hours from now and someone is going to be callin’ in the vehicle number on the inspection plate of my truck. At around nine thirty they are going to show up here.’ The Coens’ reworking of McCarthy’s prose is minimal. While maintaining the sparsity of Moss’s assessment, they evidence Moss’s pragmatism; to him, this is simple enough: he is linked to the crime scene though his abandoned truck and so Carla Jean must be sent to safety within Odessa, to remain alongside her ailing mother.

The narrative structure of No Country for Old Men is also another marked departure from McCarthy’s preceding works. By centring the narrative upon the two-points of pursuit and escape, McCarthy produces a hunter-prey dynamic within the text, with either action forcing each character of the narrative to journey the road. Stephen Tatum briefly comments that the central narrative of No Country for Old Men is a ‘pursuit-and-escape plot involving Anton Chigurh and Llewelyn Moss’[8]; however, McCarthy’s plot centres upon a tryptic of perspectives, not two, each of which detail a stage of the pursuit: shifting between Moss’s escape, Chigurh’s tracking, and Bell’s investigation into the violence stemming from the pair’s conflict. Tatum’s point is accurate, the ‘main’[9] pursuit is primarily between Moss and Chigurh, with Bell following the trail of the pair; however, it is the interplay and exchanges between the three characters that creates McCarthy’s landscape, repeating environments through the alternating perspectives. The structure of No Country for Old Men is dependent upon pursuit, and the ever evolving positions of the hunter and prey, a point affirmed by Kenneth Lincoln, as he states that McCarthy ‘quick-cuts from pursuers to pursued’[10]. Through transitioning between the three perspectives of Bell, Moss, and Chigurh, McCarthy combines both the progressive movement of pursuit with a cyclical, almost stagnant, travel, as developed through the reflective position of Sheriff Bell. While the escape and pursuit enacted by Moss and Chigurh, respectively, is clearly progressive, with the act of travelling the road central to the narrative, Bell’s monologues, on the other hand, break from the travel of the chase for a reflective assessment upon the period’s changing times. Indeed, while Bell’s monologues are typically elided or omitted entirely from the adaption, Bell remains the voice of reason, of commentary, within the work.

Steven Frye aptly summarises Bell’s position following his retirement, as stated ‘the world is rife with violence that he is drawn to contemplate and understand’[11]; however, this reflective stance from Bell is explored throughout each of his monologues, enacting his own desire ‘to hear about the old timers’ (64) through his nostalgia. While these monologues open each of the text’s thirteen chapters, only three specifically detail the central pursuit: beginning with chapter nine, in the aftermath of Moss’s death, Bell concludes his investigation with the assertion that Chigurh’s movements are that of ‘a ghost’ (248); the close of the introduction to chapter ten is a brief mention upon his return to the initial crime scene, before Bell’s journey to, and meeting with, Moss’s father, in chapter eleven. With this point in mind, it is possible to see McCarthy’s use of Bell’s opening sections as a form of separation from the events on the road. On the other hand, the monologues that focus upon the central conflict produce a comparative assessment, reflecting upon past times before returning to the violence of the current pursuit, and vice-versa. For example, following Chigurh’s execution of two employees of the Matacumbe Petroleum Group, at the desert crime scene, he re-joins the road by travelling ‘up out of the caldera and back toward the highway’ (61). McCarthy follows this scene of violence with Bell detailing a brief history of law enforcement, with the standout point that ‘some of the old time sheriffs wouldn’t even carry a firearm’ (63), breaking from the current violence to dwell upon a seemingly peaceful period. With the narrative constructed of interspersed sections, the reflective monologues bring out the extremity of the terrain’s current violence, to which Bell now investigates. It is through Bell’s recollections that McCarthy highlights the extent of the present violence enacted along the road, a violence which serves as the catalyst for Bell’s own travel, and is, ultimately, beyond his comprehension.

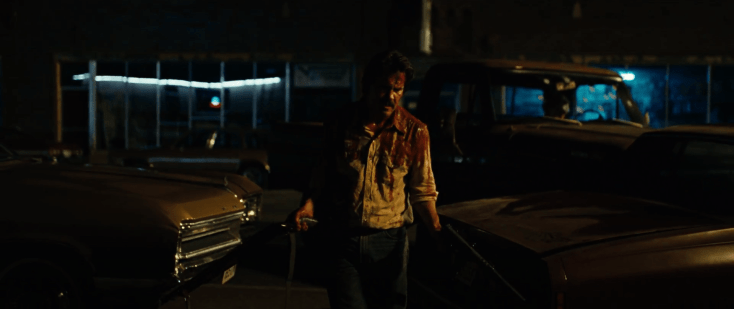

Richard Marius, writer of Sacred Violence: A Reader’s Companion to Cormac McCarthy, states that ‘McCarthy’s protagonists are always in motion, always going somewhere’[12] , a summation that defines McCarthy’s individual, specifically when applied to Llewelyn Moss. Further to this, Marius definition also seems an apt summation of the Coens’ protagonists: from convenience store robbery Herbert I. “Hi” McDunnough (Nicolas Cage), by way of the odyssey of escaped convicts Ulysses Everett McGill (George Clooney), Delmar O’Donnell (Tim Blake Nelson) and Pete (John Turturro), through to the intrepid travails of Mattie Ross (Hailee Steinfeld), the brothers’ protagonists are often driven to travel. For Moss is, and while not having an initial set destination, indeed travelling, as proposed by Marius, ‘somewhere’, specifically to ‘El Paso’ (231), Texas. McCarthy presents an overarching question to Moss’s travel, one which can be traced back to a passing remark from Carla Jean, as stated ‘What did you give for that thing?’(21), made after seeing the acquired ‘pistol’ (21) of Moss’s desert plunder. McCarthy and the Coens presents an answer to the question through the drastic upheaval of Moss’s existence, and the inevitable fatal consequences of his escape. Indeed, Moss maintains a constant travel, with the sole objective of eluding the multiple parties of the authorities, the Matacumbe Petroleum Group, represented initially by Chigurh, and then by Wells, and, finally, Pablo Acosta’s trackers. This escalation develops, and stresses, the threat of the latter two groups in Llewelyn’s reflective realisation at the Trail Motel, as outlined:

There were probably at least two parties looking for him and whichever one this was it wasn’t the other and the other wasn’t going away either. [87]

For the Coens and Brolin, this is conveyed simply with a silent pause. As previously noted, the journey of McCarthy traveller typically undergoes an escalation into a base struggle for survival, with the individual falling into desperation, following the failure of an original purpose or objective. Here, in No Country for Old Men, McCarthy, instead, inverts the precedent. Moss’s travel is, instead, initiated by such an attempt, survival being the catalyst for his journey. The protagonist’s escape, however, is ultimately fruitless, as stated ‘It had already occurred to him that he would probably never be safe again in his life’ (108-109). With this in mind, it is possible to assess that McCarthy constructs Moss’s travel from the combination of two conflicting points: that of his objective, survival, and the inevitable futility of his endeavour. The latter of which is highlighted by Carson Wells. The conversation between the pair of Moss and Wells serves as an insight into the former’s pursuers; indeed, the latter’s emphasis upon the relentlessness of the trackers clearly defines the inevitable outcome to Moss’s travel, re-enforcing Bell’s earlier concerns, as expressed to Carla Jean, that ‘These people will kill him [Moss] […] They wont quit’ (127).

McCarthy places Wells in a somewhat liminal position within the narrative: while an employee of the Matacumbe Petroleum Group, and rather straightforwardly labelled as ‘a hit man’ (156), he is also, like Moss, a veteran of war, commenting upon his service in the ‘special forces’ (156). From this position, Wells grounds Moss’s travel in a bleak reality, confirming previous speculations and presumptions by elaborating upon the phantom-like collectives in pursuit, emphasising the very present and extreme violence facing Moss. This, subsequently, confirms Moss’s earlier assessment of there being ‘probably at least two parties looking for him’ (87) and that ‘he would probably never be safe again’ (109), through a single statement:

This isnt going to go away. Even if you got lucky and took out one or two people — which is unlikely — they’d just send someone else. Nothing would change. They’ll still find you. There’s nowhere to go [156]

This extract perfectly encapsulates Wells’s message: Moss is outnumbered, without a clear point of escape, and, despite Moss’s earlier acknowledgment that ‘at some point he was going to have to quit running on luck’ (108), Wells re-affirms the fact that such luck (156) cannot withstand these resources. Within this, Wells places Moss’s escape into perspective, detailing the advanced skill sets of the pursuers, in regards to both tracking and enacting violence, as stated:

What makes you think I wont disappear?

Do you know how long it took me to find you?

No.

About three hours.

You might not get so lucky again.

No, I might not. But that wouldn’t be good news for you. [152]

Here, Wells outlines an inevitable truth: that Moss cannot elude pursuit. It is this point that subsequently forces Moss to take Wells up on his offer of protection (157), with the former confiding in Carla Jean that ‘I’ve got a number here I can call. Somebody that can help us’ (182). This realisation comes too late for Moss, attempting to contact Wells following the latter’s own execution, a victim of the warned violence of Anton Chigurh. Wells’s death subsequently forces Moss to continue his travel along the road, unable to bargain with Chigurh’s single offer: by leaving the money, Moss ensures Carla Jean’s safety, at the cost of the fortune and his life, as is stated ‘bring me the money and I’ll let her walk. Otherwise she’s accountable […] I wont tell you you can save yourself because you cant’ (184). Wells’s offer served as a means of escape for Moss, a conclusive end to his own travel and to the threat of Chigurh’s pursuit, as pointed out in the former’s assertion that he could ‘make him [Chigurh] go away’ (148). Chigurh’s offer, on the other hand, only serves to re-affirm Wells’s warning, itself another reminder of the pressing threat of violence from those in pursuit. This, alongside the futility of escape, as covered in Wells’s assessment, causes Moss’s travel to become his existence, to no foreseeable end or evident benefit. He is forced to journey the road due to the encroaching danger from his pursuers, enacting the constant travel, or ‘motion’, as highlighted in Marius’s critique. The function of Moss’s escape is to ensure his own survival, a point that is repeatedly stated to be unachievable under his circumstances, and is proven as such.

Of the multiple functions of travel explored within McCarthy’s oeuvre, tracking is a consistent feature: from the Kid’s trace reading of the Glanton gang’s trail in Blood Meridian, to the father and son’s cautionary travel in The Road; with the latter pair’s attempts to conceal their trace inverting the predominant perspective from the tracker, to the tracked. No Country for Old Men, however, is a combination of the two, bringing the features of both pursuit and escape to the novel’s forefront. While McCarthy retains instances of trail reading that are characteristic of the earlier ‘Western’ works, No Country for Old Men marks a shift within the trope of tracking through the inclusion of technology. The first examples of tracking in No Country for Old Men are, however, a continuation of those of McCarthy’s Western narratives: trail reading from an imprint, or trace {NOTE: cf. Gwinner, p.139}[13]. This form of tracking is enacted during both Moss’s and Sheriff Ed Tom Bell’s separate investigations into the aftermath of the desert cartel exchange; the former tracks the single trace of the ‘last man standing’ (15), shifting between the blood trail of the survivor and repeatedly scanning the landscape for points of guidance, with his binoculars. In this form of tracking, McCarthy asserts the character’s position as a hunter (11), and can be assessed as something of a return to the Kid’s tracking in Blood Meridian, as stated ‘he went on, following the tracks with their suggestion or pursuit and darkness’[14]. This ‘suggestion of pursuit’ is found, also, in Moss’s reading of the survivor’s trace, as the man’s travel is clearly presented as an attempt at escape, as highlighted:

He cut for sign a hundred feet to the south. He picked up the man’s trail and followed it until he came to blood in the grass. Then more blood. You aint going far, he said. You may think you are. But you aint. [15]

The Kid’s pragmatic approach to the Glanton gang’s trail, sorting out ‘single riders’[15] and reading both ‘their number’ and pace (227-228), is repeated here through Moss’s understanding of the man’s condition. In a similar three point assessment, Moss identifies that the man is injured, that he is ‘shaded up somewheres’ (15), and that ‘nothin wounded goes uphill’ (16), deducing the actual distance the survivor could, realistically, travel. It is through this awareness that McCarthy portrays Moss as a competent, and experienced, tracker, with his reading of the man’s trail echoing that of his earlier antelope prey, assessing the landscape from the vantage point of a ‘ridge’ (8, 16).

During his tracking of the survivor, Moss clearly utilises his hunting experience, breaking from the track in order to avoid the seemingly inevitable conflict from following another’s trail, as stated ‘the chances of me seein you fore you see me are about as close to nothin as you can get’ (15-16). Indeed, the possibility of conflict extends into Bell’s perspective of the scene. While Moss tracks a single individual, Bell, on the other hand, investigates the aftermath as a whole, and shares Moss’s caution. Moss and Bell face an issue experienced by all of McCarthy’s trackers: the uncertainty as to what they may find at a trail’s end. This point is apparent during Wendell and Bell’s dialogue prior to reaching the vehicles, as the latter responds to the former’s question of ‘what do you reckon it is we’re fixin to find down here?’(71), with the defeated ‘I don’t know’ (71). Despite the uncertainty to Bell’s point, he is shown to be an experienced track reader, able to interpret the tire trails leading to the scene, as stated:

Bell pointed at the ground from time to time. You can tell the day tracks from the night ones, he said. They were drivin out here with no lights. See there how crooked the track is? (…) It’s the same tire tread comin back as was goin down. Made about the same time [70-71]

This extract is reminiscent, again, of the Kid’s tracking of the Glanton gang, as, while Bell is investigating a trace rather than pursuing one, both display a similar assessment, as stated:

He followed the trace for several miles and he could tell by the alteration of tracks ridden over that all these riders had passed together and he could tell by the small rocks overturned and holes stepped into that they had passed in the night. [227-228]

It is through the individual’s ability to identify specific details of another’s trace that the action of tracking becomes a central aspect to the functions of travel for McCarthy’s characters. In order to convey this trope within McCarthy’s fiction, the Coens utilise extreme close-ups which centre solely upon trace, tracks or implements in aid of track another. Several images within this article show examples of this.

Bell and Wendell’s investigation of the scene details individual pieces of trace, from which they map-out the movements of the traders, ranging from ‘old Mexican brown dope’ (73) to the ‘shell-casings’ (74) of varied weapon calibres of ‘nine millimetre’ (75) rounds to ‘a couple of .45 ACPs’ (75). From this evidence, the pair deduce that ‘It dont much stand to reason that the last man never even got hit’ (76), before setting out and, subsequently, finding the deceased’s location. In this focus upon trace, through the tracking undertaken by Moss and Bell, No Country for Old Men is clearly placed within the latter band of Edwin T. Arnold’s proposed geographical divide of McCarthy’s ‘‘Southern’ and ‘Western’ books’[16], to a noticeable extent. However, No Country for Old Men is not a clear-cut continuation of the ‘Western’ trope, as the examples of tracking develop, and advance, from that of precedent. It is important to note that McCarthy begins with the ‘etched […] pictographs’(11) of hunters along the rocks of the desert, sighted during Moss’s antelope hunt, before moving to Bell’s investigation, and then onto a new form of pursuit, assisted by technology, as carried out by Anton Chigurh. This progression marks an increase in the threat posed by the tracker through the precision with which to pursue the individual. With each of the three principle characters enacting a form of tracking or hunting, the action becomes a central aspect to the functions of travel in No Country for Old Men.

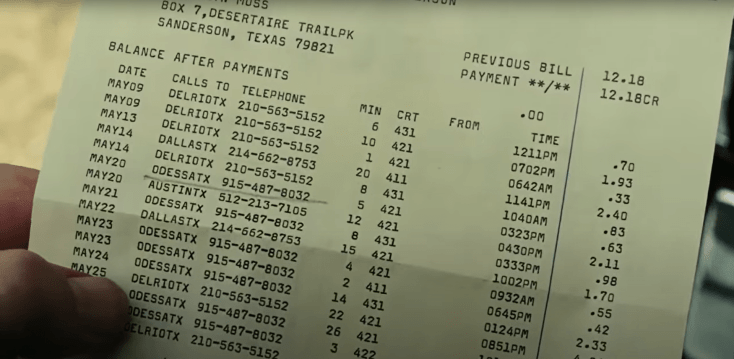

Brian Evenson’s criticism upon the subject of nomadology within McCarthy’s fiction, published in 1995, provides an overview of the populaces of McCarthy’s landscapes, identifying the individuals as a collection of ‘renegades, lone wolves, outcasts, self-imposed exiles, foreigners, wanderers, killers[17]. Evenson places these titles within the three overarching ‘categories’ (41) of ‘Tramps’, ‘Spirited Unfortunates’, and ‘Nomads’[18]; each of which detail the individual’s relation to society. While each of Evenson’s titles accurately identify consistent characteristics of McCarthy’s individuals as travellers, with the titles suggesting a separation and a subsequent movement away from society, he avoids any mention of the tracker or hunter position. These two titles are prominent throughout McCarthy’s work, even at the time of the criticism’s publication, and are explored thoroughly in No Country for Old Men. While McCarthy’s earlier works, specifically Blood Meridian, detailed the action of track reading, Evenson’s omission of the ‘tracker’ should be revised in light of No Country for Old Men’s publication, and the character of Anton Chigurh. With Chigurh, McCarthy subverts the previous examples of tracking by removing the action of following a physical trace; instead, the tracker is lead to a specific destination, as shown through Chigurh’s use of ‘the signal from the transponder’ (98). It is possible to identify three key objects that are used by Chigurh during his travel: the ‘inspection plate’ (59) of Moss’s vehicle, Llewelyn’s mail, specifically the ‘phone bill’ (81) with ‘calls to Del Rio and to Odessa’ (81), and, finally, the transponder. The technological advancements utilised by Chigurh are in stark contrast to the methods of trail reading noted during Moss and Bell’s opening investigations. For example, the repeated point of Chigurh ‘listening’ (98) to the ‘beep’ (171) from the signal is in opposition to Moss’s visual hunt of the antelope, and the survivor; during which, with the use of the ‘twelve power German binoculars’ (8) Moss travels the landscape with caution, repeatedly watching, scanning, or glassing the terrain (8-13)[19]{NOTE: cf. Gwinner, p.139}. Chigurh’s tracking, however, lacks any such forms of vantage points, with his pursuit somewhat dependent upon the receiver, repeatedly ‘listening’ (103) and, subsequently, mapping Moss’s movements from the signal alone.

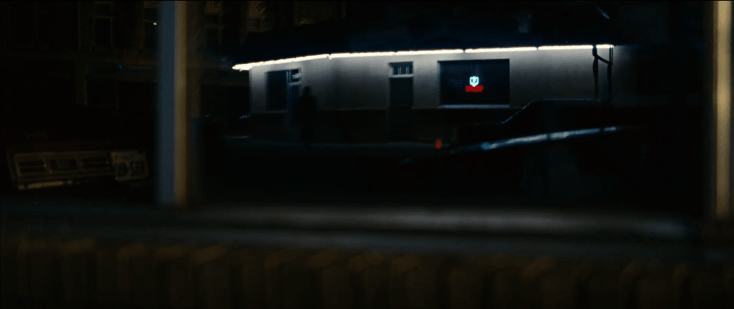

The transponder’s accuracy provides a precision to Chigurh’s travel, directing his pursuit of Moss along the road to two specific locations: the Trail Motel and the Hotel Eagle. Prior to locating the signal, however, Chigurh’s travel is somewhat directionless. Despite finding Moss’s address from the acquired inspection plate from the abandoned vehicle (59), confirming Llewelyn’s earlier speculation that the trackers would ‘be calling in the vehicle number and getting his name and address’ (36), Moss’s mobility is an obstacle to Chigurh’s pursuit. While Moss is, initially, able to elude Chigurh along the road, once the receiver locates the signal ‘just west of Del Rio’ (98) the latter’s pursuit commences, with the device providing a precision that would otherwise be absent. It is due to this accuracy that the transponder unit separates Chigurh from the traditional methods of tracking, as explored by McCarthy during Blood Meridian, to such an extent that the precision borders upon improbability. The transponder unit reduces the scale of Chigurh’s pursuit, locating the satchel within the area of Del Rio to the exact point of Moss’s first rented room, adjacent to his second, at the Trail Motel. This improbability leads to Moss’s discovery of the device at the Hotel Eagle, inspecting the satchel after noting that ‘there is no goddam way’ (107) he could be tracked to such a degree of accuracy, over the covered distance, without guidance.

At the Trail Motel, however, the stages of Chigurh’s tracking are shown; first, ‘listening’ (103) to the receiver, before finding the rented room, he executes two gunmen of unspecified allegiance, either attempting to claim or re-claim the satchel. It is suggested the pair are Acosta’s employees purely upon the points of their ethnicity, with the first identified as ‘Mexican’ (103) and the second’s Spanish dialect, pleading to Anton with ‘No me mate’ (104). With Chigurh’s process outlined, McCarthy shifts perspectives at the Hotel Eagle from the pursuer to the pursued, creating a tension through Moss’s preparation for Chigurh’s arrival. With this inverted perspective, McCarthy builds upon the preceding events at the Trail Motel, as we anticipate the inevitable violence enacted by Chigurh when locating the signal. The discovery of the transponder forces Moss to adapt, as is stated ‘He got the shotgun out of the bag and laid it on the bed […] He knew what was coming. He just didn’t know when’ (108) and it is in this instance that McCarthy highlights the integral position of the transponder to both Chigurh’s travel and Moss’s actions. Upon finding the transponder, Moss furthers his understanding of the extent of his situation, and the subsequent need to develop his travel, deducing the point that ‘he was going to have to quit running on luck’ (108). The transponder is central to the pair’s travel through, both, Chigurh’s dogged tracking of Moss, alongside the latter’s own attempts to elude and adapt to the precision of the device.

While integral to the pursuit of Moss, it is apparent that Chigurh’s travel is not centred singularly upon the transponder’s signal. McCarthy highlights, throughout the pursuit, Chigurh’s ability to utilise multiple forms of trace: beginning with the inspection plate, and Moss’s phone bill, he then picks up the receiver’s signal, before returning to the phone log to track Carla Jean’s calls to ‘Odessa’ (81).

This is discussed during the dialogue between Moss and Wells, as the latter warns that the loss of the transponder will not prevent, nor deter, Chigurh in his pursuit, as outlined:

How do you think he found you?

[…] I know how he found me. He wont do it again.

[…] It’s called a transponder, Wells said.

I know what it’s called.

It’s not the only way he has of finding you. [154]

Once locating the ‘sending unit in the drawer of the bedside table’ (172) at the Hotel Eagle, removed from the satchel by Moss, Chigurh radically alters his pursuit, as warned by Wells in the final line of the above extract. While the objective of his travel continues to be an attempt to secure the satchel, Chigurh responds to the loss of the transponder by subverting the hunter-prey structure, through the inclusion of Carla Jean:

Do you know where I’m going?

Why would I care where you’re going?

Do you know where I’m going?

Moss didn’t answer.

[…] I know where you are.

Yeah? Where am I?

You’re in the hospital at Piedras Negras. But that’s not where I’m going. Do you know where I’m going?

Yeah. I know where you’re goin.

[…] You know they won’t be up there.

It doesn’t make any difference where they are. [183-184]

With Carla Jean’s newly assigned accountability (184), McCarthy concludes the ‘main pursuit-and-escape plot’[20], as titled by Tatum, shifting Chigurh’s pursuit from the mobile, and versatile, Moss, to the somewhat stagnant Carla Jean, by comparison. It is through the extract’s exchange that McCarthy displays Chigurh’s strategic mind-set, enacting the ‘principles’ (153) that transition his travel from a dogged obsession for the satchel to the personal point of ruining Moss. Here, the Coens, in their penchant use of singles, frame Chigurh and Moss as contrasts throughout the negotiation. The former, with his feet placed atop Wells’s bed in order to avoid the pooling blood sluicing across the floor, is calm, unperturbed by the situation. Moss, on the other hand, is still, unmoving as Chigurh narrates his next steps. Chigurh terms are exactly that, the ‘best deal’ Moss can hope for. As the Coens frame Moss’s stock-still frame, we see a man unable to move: even as Chigurh threatens him with his inevitable end, Moss is stuck within a mire of his own making. Ultimately, the Coens’ framing of the scene conveys the encroaching threat of Chigurh. With the strict parameters set, Moss may only listen to what is to come.

At this stage, the previously stated use of mail, specifically that of Llewelyn and Carla Jean’s, becomes central to the travel of Chigurh, directing him along the road from destination-to-destination. This form of tracking is apparent at the home of Carla Jean’s mother, with Chigurh again searching ‘the phone bill […] down the list of calls’ (205), identifying the ‘Terrell County Sheriff’s Department’ (205). Indeed, this trace of ‘mail’ (205) replaces that of the earlier trail tracked by Moss and Bell, and the ‘Western’ texts of Blood Meridian and The Border Trilogy. Following Chigurh’s threat of pursuing Carla Jean, both his and Moss’s travel is drastically altered. The central hunter-prey format to the pair’s travel is inverted, as Chigurh now attempts to control Moss’s escape, concluding his pursuit, in order to draw his prey to him (176). While Moss attempts to reassume his original title of the ‘hunter’ (11), threatening Chigurh with his own violence, as stated ‘I’ve decided to make you a special project of mine. You aint goin to have to look for me at all.’ (185). Despite this alteration, the action of either pursuit or escape continues to be the central function to the individual’s travel, with McCarthy assigning new positions, alongside altering those already established, to characters within a power struggle structured upon the two objectives.

Stephen Tatum’s generalised assessment of travel, detailing McCarthy’s stylistic approach to the individual’s journey in No Country for Old Men, is, to an extent, inaccurate, as he states:

As we can see with the first line that opens nearly all of the novel’s sequences, Chigurh never journeys, which is to say he departs, travels, and then arrives somewhere. He — like the other characters in the novel — is always arriving somewhere, the temporal duration of the journey compressed or entirely elided in McCarthy’s screenplay-like narration[21]

Through the use of multiple perspectives, McCarthy and the Coens reduce the focus upon the individual travelling the road, as seen within The Border Trilogy and The Road. Here, in No Country, scenes of travel are often condensed to a brief departure-arrival structure, as outlined by Tatum, and are shown in such instances as Bell’s call to the burning vehicle, as stated ‘Let me get my coat. […] They pulled off the road at the gate’ (67-68). However, to propose that all instances of travel are either ‘compressed’, or omitted completely, is something of a misstep, as McCarthy combines these aptly labelled ‘screenplay-like’ shifts with an in-depth focus upon the individual’s journey. For instance, following Chigurh’s injury at the Hotel Eagle, McCarthy documents his travel to the ‘clinic outside Bracketville’ (161) with great depth, as stated, ‘He drove to the crossroads at La Pryor and took the road north to Uvalde […] On the highway outside of Uvalde he pulled up in front of the Cooperative.’ (161). McCarthy continues, documenting Chigurh’s second journey to ‘the drugstore on Main’ (162), stating ‘He drove down Main Street and turned north on Getty and east again on Nopal where he parked’ (162), before concluding with Chigurh reaching his destination of ‘a motel outside of Hondo’ (163). Here, the stages of travel are apparent, but are elided by the Coens; McCarthy cites street names, directions, and the destinations of the clinic, drugstore, and motel, to such an extent that Chigurh’s journey becomes the central focus of this section of the narrative. Indeed, it is the Coens, rather than McCarthy, that often compress or elide instances of travel. Such is the nature of Chigurh or Moss that it is the danger of stopping which instils the sense of dread and fear for the audience. Any superflous instances of travel are keenly omitted entirely.

In a broader assessment on McCarthy’s stylistic approach to travel, specifically in No Country for Old Men, it is important to note the effect of the fractured narrative. With McCarthy constantly leaving and returning to multiple journeys, accurately summarised in Lincoln’s earlier note that the narrative ‘quick-cuts from pursuers to pursued’[22], the travel of a single individual is interspersed with that of several others, separating a single journey into divided sequences. For example, following Chigurh’s departure from the motel (166), McCarthy returns to both Wells’s and Bell’s narratives, with the former investigating Moss’s blood trail and ‘bootprints’ (167) along the bridge into Piedras Negras, and the latter, ‘totting up figures on a hand calculator’ (167). Following these sections, McCarthy returns to Chigurh travelling, regaining the signal ‘Some two miles past the junction of 481 and 57’ (170), before arriving at the destination of the Hotel Eagle, and therefore completing Tatum’s three-point structure of departure, travel, and arrival, over a disjointed sequence. Certain instances of travel are reduced or condensed in No Country for Old Men, as McCarthy typically presents the characters departing and arriving at a destination, over that of an extensive focus upon the travel itself. Tatum’s comment, however, avoids mention of the fractured narrative and the subsequent completion of the three-point structure during the individual’s journey. It is due to this omission that Tatum’s critique falls into inaccuracy; McCarthy’s characters complete the outlined structure to travel, albeit through fractured sequences.

As previously outlined, No Country for Old Men marks something of a departure from McCarthy’s preceding works, specifically in regards to the narrative’s multiple perspectives, and its 1980s setting. The road is also, to an extent, another example of McCarthy’s separation from his earlier fiction, as, while sharing The Crossing’s emphasis upon the road’s centrality to the individual’s travel, No Country for Old Men ties the road explicitly to the subject of war. Steven Frye aptly summarises No Country for Old Men as a ‘further exploration of the nature and reach of human violence’[23] from that within The Border Trilogy; an exploration enacted along the road through Bell’s investigation. The affinity between the subject of war and McCarthy’s fiction is apparent within each work, ranging from the war-services of veterans, to the ‘white light’[24] of the desert nuclear test at The Crossing’s conclusion {NOTE: cf. Guillemin, p.105}. However, none display the impact of war as thoroughly as No Country for Old Men, with the road itself becoming a ‘warzone’ (240). Indeed, the road is a combined scene of both a vanishing social order and conflict, with Bell’s attempts to ensure the protection of ‘a couple of kids’ (194), Llewelyn and Carla Jean, from the central pursuit’s constant violence.

No Country for Old Men marks a return to the veteran traveller of war, as shown throughout Blood Meridian, with the Man’s confession to having ‘been at war’[25] repeated here through Moss, Bell, and Wells’s recollections of their wartime services. This point is assessed in Dan Flory’s criticism upon the Coen brothers’ 2007 film adaption of the novel, in which he states that the principle characters ‘were trained to become killers’[26], indeed a first for McCarthy and the brothers’ protagonists. The landscape here is traversed by veterans of both the ‘European theatre’ (294), of World War Two, as shown through Bell’s service — an attribute omitted by the Coens —, and the Vietnam War, from the ‘special forces’ (156) to the Army Infantry (188); all of whom are now participating within the ‘out and out war’ (134) of the borderland drug trade. The conflict at the centre of No Country for Old Men is the outcome of the disputes between two ‘rival’ (96) parties, and it is within this context, and setting, that the two objectives of pursuit and escape are clearly paramount to the individuals’ travel, with the road serving as the only possible means to enact both intentions. For Moss, arguably another everyman of the Coens’, while adept and proficient at hunting, he cannot battle the mounting hunters in pursuit. In truth, Moss, in his misunderstanding of those hunting him, fatally underestimates the cost of taking that cursed boon of that black satchel.

[1] Dianne C. Luce, Border Trilogy’s Vanishing World, in A Cormac McCarthy Companion: The Border Trilogy, edt. Edwin T. Arnold and Dianne C. Luce, (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2001), p.162.

[2] McCarthy, The Crossing, p. 426.

[3] Cormac McCarthy, All the Pretty Horses [1993], in The Border Trilogy, (London: Picador, 2002), p.166.

[4] Ibid,p.167.

[5] Edwin T. Arnold, McCarthy and the Sacred: A Reading of The Crossing, in Cormac McCarthy: New Directions, edt. James D. Lilley, (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2002), p. 227.

[6] Cormac McCarthy, No Country for Old Men [2005], (London: Picador, 2011), p.94.

[7] Kenneth Lincoln, American Canticles, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008),p. 146.

[8] Stephen Tatum, “Mercantile Ethics”: No Country for Old Men and the Narcocorndo, in Cormac McCarthy: All the Pretty Horses, No Country for Old Men, The Road, edt. Sara Spurgeon, (London: Continuum, 2011), p.77.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Kenneth Lincoln, American Canticles, (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008),p. 147.

[11] Steven Frye, Understanding Cormac McCarthy, (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2009), p. 158.

[12] Richard Marius, Suttree as a window to the soul of Cormac McCarthy, in Sacred Violence: A Reader’s Companion to Cormac McCarthy, eds., Hall and Wallach, (El Paso: University of Texas at El Paso, 1995), p.15.

[13] Donovan Gwinner provides a definition for ‘cut for sign’, a ‘tracking term’ I learned from Gwinner’s criticism, in Donovan Gwinner, Everything uncoupled from its shoring: Quandaries of Epistemology and Ethics in The Road, in Cormac McCarthy: All the Pretty Horses, No Country for Old Men, The Road, edt. Sara Spurgeon, (London: Continuum, 2011), p.139.

[14] Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian [1985], (London: Picador, 2010), p.228.

[15] Ibid, p.227-228.

[16] Edwin T. Arnold, The Mosaic of McCarthy’s Fiction, in Sacred Violence: A Reader’s Companion to Cormac McCarthy, eds., Hall and Wallach, (El Paso: University of Texas at El Paso, 1995), p. 17.

[17] Brian Evenson, McCarthy’s Wanderers: Nomadology, Violence, and Open Country, in Sacred Violence: A Reader’s Companion to Cormac McCarthy, edt. Wade Hall & Rick Wallach, (El Paso: University of Texas at El Paso, 1995), p.41.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Donovan Gwinner, Everything uncoupled from its shoring: Quandaries of Epistemology and Ethics in The Road, in Cormac McCarthy: All the Pretty Horses, No Country for Old Men, The Road, edt. Sara Spurgeon, (London: Continuum, 2011), p. 139.

[20] Stephen Tatum, “Mercantile Ethics”: No Country for Old Men and the Narcocorndo, in Cormac McCarthy: All the Pretty Horses, No Country for Old Men, The Road, edt. Sara Spurgeon, (London: Continuum, 2011), p.77.

[21] Tatum, p. 89.

[22] Lincoln, Canticles, p. 147.

[23] Frye, Understanding, p,155.

[24] McCarthy, The Crossing, p. 740.

[25] McCarthy, Blood Meridian, p. 332

[26] Dan Flory, Evil, Mood, and Reflection in the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men, in Cormac McCarthy: All the Pretty Horses, No Country for Old Men, The Road, edt. Sara Spurgeon, (London: Continuum, 2011), p. 129.

Leave a comment