“Lucky” Ned Pepper’s name is uttered with trepidation throughout Joel and Ethan Coen’s faithful adaption (2010) of Charles Portis’s formative Western-bildungsroman True Grit (1968) as if it were a means by which to summon the ruthless brigand to the speaker’s door. However, it is not until an hour into the film that “Lucky” Ned (played with snarling intensity by Barry Pepper) and his feared-gang are sighted before a hushed Mattie Ross (Hailee Steinfeld) and her employed bounty-hunter, Deputy U.S Marshall Rooster Cogburn (Jeff Bridges). As the pair lie-in wait above a makeshift dug-out of the unseen hunter ‘Greaser Bob’, “Lucky” Ned rides into the clearing before the hut, his legs quilted within ‘wooly chaps’ as white as candle-sticks. While the myth surrounding the Gang creates the image of a ruthless murderer, “Lucky” Ned is eventually shown to be a somewhat peaceable, even even-handed, and yet by far the deadliest wanted-man pitted against the implacable Cogburn. In truth, with True Grit, and while not the typical incarnation of evil as the Coen’s usually include within their Western works, “Lucky” Ned, as he is within Portis’s novel, is shown to be both the mythical storybook brigand of the rumours and a man who prioritises pragmatism and fairness above all else.

Portis’s seminal Western charts the indefatigable fourteen-year old Ross’s odyssey into the Choctaw Nation during the winter of 1878. Employing the ‘meanest’ marshal money can buy, the brutal Rooster Cogburn, a man defined as ‘pitiless’ and ‘double-tough’, Ross sets out, in-tow of Cogburn, to avenge her father’s killer, the desperate cowardly killer, Tom Chaney (Josh Brolin). Also in pursuit is the windbag Texas Ranger LaBeouf (played with wonderful pomp and grandiosity by Matt Damon), who has been ‘ineffectually’ hunting Chaney for a previous murder of a State-Senator committed within Waco, Texas. Together, this uneasy triad, having coalesced to join their efforts in pursuit of Chaney, strike out for the territories during ‘wintertime’ to avenge Ross’s father and the slain Senator Bibbs. Through the pursuit of Chaney, Portis analyses the subject of the fabled myth of the American West in stark clarity: while the likes of Cogburn and “Lucky” Ned live up to their infamy, Chaney is ultimately shown to be little more than a vagrant opportunist, with as little intellect as he has money within his threadbare-pocket. This is, in essence, one of the principle focuses of novel and the Coens’ adaption: that of the nature storytelling. As is outlined within Ross’s opening reflection of her pursuit of Chaney, she opines that listeners of her tale cast doubt upon the validity of her hunt. Immediately, as was noted by Emily Temple, there is a meta-narrative[1] in play within the opening sentence of Portis’s novel: Ross is telling her own story set within a fabled history of the unclaimed American West. Her testimony is itself a tall-tale of retribution within a well populated history of such stories. We, despite her erstwhile audiences, are skeptical. In a way, Ross’s testimony, if you will, of Portis’s True Grit is told in search of credence. Ross, from the outset, with her dogged determination is outlining the moral standard with which she wishes to uphold and wishes of her audience in accepting her tale. However, her journey into the Choctaw Nation casts her against raconteurs, wastrels, itinerants, killers, and nincompoops who populate both Portis’s novel and the Coens’ oeuvre.

“Lucky” Ned Pepper is an amalgam of the outlaw tropes typical of the Western genre. He is the typically feared chieftain of a small band of thieves whose ambulatory existence is still keeping Cogburn from his hovel and his bottle at the rear of Lee’s store; his name strikes an equal-measure of fear into those who utter it and those who hear it; his aspect is shattered by a bullet owing to Cogburn’s temperamental trigger-finger; his ‘woolly-chaps’ are equally a trademark as they are a preposterous extravagance; and he is the nemesis to the marshal in pursuit. So far one would assume a simple antagonist easily conjured by Portis. However, “Lucky” Ned pragmatic approach to his Gang’s flight coupled with his amicable treatment of Ross seemingly counters the mythos surrounding the notorious thief. As Ross is captured by “Lucky” Ned, we see the harried raider for the first time — extract excised from the novel:

He flung me to the ground and put a boot on my neck to hold me while he reloaded his rifle from a cartridge belt. He shouted out, “Rooster, can you hear me?” There was no reply. The Original Greaser was standing there with us and he broke the silence by firing down the hill. Lucky Ned Pepper shouted, “You answer me, Rooster! I will kill this girl! You know I will do it!”

Rooster called up from below, “The girl is nothing to me! She is a runaway from Arkansas!”

“That’s very well!” said Lucky Ned Pepper. “Do you advise me to kill her?”

“Do what you think is best, Ned!” replied Rooster. “She is nothing to me but a lost child! Think it over first.”

“I have already thought it over! You and Potter get mounted double fast! If I see you riding over that bald ridge to the northwest I will spare the girl! You have five minutes!”

“We will need more time!”

“I will not give you any more!”

“There will be a party of marshals in here soon, Ned! Let me have Chaney and the girl and I will mislead them for six hours!”

“Too thin, Rooster! Too thin! I won’t trust you!”

“I will cover you till dark!”

“Your five minutes is running! No more talk!” Lucky Ned Pepper pulled me to my feet.

Save for the italicized lines, the presence of the Original Greaser Bob and the replacement of “Lucky” Ned’s Remington rifle with a Remington 1875 revolver, the Coens’ adaption of Portis’s work is strikingly devoted to the novel. To me, this scene, rather than Cogburn’s charge-against the galloping Gang encapsulates the pair’s violent shared history: With Ross pinned to the ground beneath “Lucky” Ned’s well-worn boot, the following line is snarled by her captor: “Tell me another lie and I will stove in your head!”. Within the novel, Portis then notes an observation about the bandit from Ross:

Part of his upper lip was missing, a sort of gap on one side that caused him to make a whistling noise as he spoke. Three or four teeth were broken off there as well, yet he made himself clearly understood

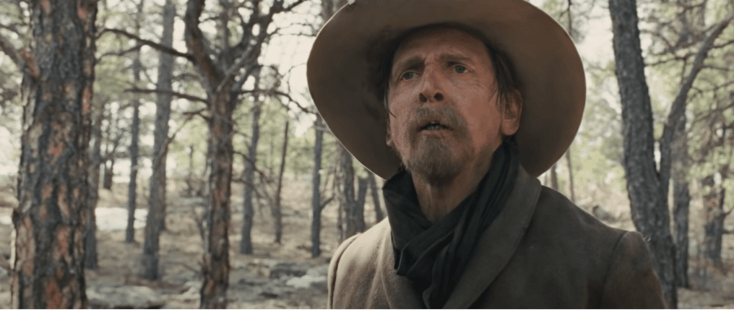

With the Coens and their DP Roger Deakins, their wide-angel lens draws into “Lucky” Ned’s fractured aspect for the first time. With his Remington pistol pointing down towards Ross, at the mention of Cogburn’s presence, the camera cuts to a close-single shot of “Lucky” Ned’s rage, growling with a whispered hushed the despised name of his pursuer. His maimed jaw — the work of Oscar-winning make-up artist Christien Tinsely — in-plain-sight, as if the mention of “Lucky” Ned’s hunter aggravates injury the marshal himself inflicted. The ensuing dialogue is a game of brinkmanship between the hunter and his prey: while Cogburn distances himself from knowing the girl, “Lucky” Ned seeks advice on whether he should shoot the child. The unseen Cogburn then challenges “Lucky” Ned to ‘think it over first’, challenging his opponent to spend time on the decision. Hunted as he is, “Lucky” Ned switches his focus: he does not have the time, and so immediately calls for Cogburn to depart. Now, in place of “Lucky” Ned following Cogburn’s advice, he sets a ‘five minutes’ deadline for Cogburn to clear the area; if “Lucky” Ned’s imperative is followed, Ross will be spared. The pair’s long-standing war, conveyed here through their bartering and bluffing game of brinkmanship, is one of understanding the other: while, indeed, “Lucky” Ned is Ross’s captor, Cogburn is aware that the bandit is as likely to kill the girl as he is to let her live. Despite the rumour which has preceded his entrance, “Lucky” Ned lives by some semblance of a moral-code, even if it remains undisclosed.

What follows this distant stand-off between Cogburn and “Lucky” Ned, hunter and prey, respectively, is then Ross’s conference with the bandit chieftain. Here, breaking from the precedent, Pepper is cordial and even polite to his prisoner, offering her coffee before they hold council. In truth, without Chaney in-tow the Gang would not have been embroiled within Cogburn’s pursuit. As a result, “Lucky” Ned is evidently ambivalent to Chaney, and, seemingly, shows more respect for his companion’s hunter than he does for the pursued himself. By the time the Gang leave their ‘rock-ledge’ hideout, “Lucky” Ned has left Chaney vague details to meet at ‘The Old Place’ and then he to his pursuer. As is typical of the Coens, their trimming of the bandit’s dialogue with Ross from the novel is an exercise in brevity and pacing. Within the film, we are not afforded the subjective perspective of Ross’s presumptions towards “Lucky” Ned: we do not hear of his illiteracy, or a suspected juvenile proclivity towards being ‘mean to cats’ or making ‘rude noises in church’ when a child. Instead, the Coen’s adaption of “Lucky” Ned is one centred upon his pragmatism: with Cogburn in pursuit, there is little time to divide the Gang’s earnings between its members or for Ross to serve as a signee to their boon. With the Coens, “Lucky” Ned is simply wishing to leave before Cogburn returns from the west.

While Barry Pepper has noted the need for the Coens’ to excise “Lucky” Ned’s history, the rhymical cadence of both the source material and the Coens’ adaption produces a dialogue that is almost Shakespearean, as he states that the dialogue is ‘like an American Shakespeare it has this iambic pentameter and musicality and rhythm to it’[2]. Pepper’s somewhat lisping-roar highlights both his contempt for Cogburn and his injury: while we do not hear of how he was injured within the film, Pepper, with his guttural and husky delivery, conveys the wound as not only a permanent scar of his history with Cogburn, but that each word he utters is in some way affected by his nemesis. Indeed, Pepper’s performance is one of striking rage and serene calm, at once the calculating bank-robber of the tales and a man harried and hunted across the plains. Despite the little screen-time Cogburn’s nemesis is given, his mark is indelible when reflecting upon Ross’s odyssey for retribution, as he distinguishes himself from the ‘congress of louts’ which she has faced along the way. While not the malevolent shadow of either Miller’s Crossing’s Eddie ‘Dane’ or No Country for Old Men’s Anton Chigurh, “Lucky” Ned is shown to hold a level of cautious discernment and snap-turn violence akin to both men. Not wishing to disclose True Grit’s standoff, “Lucky” Ned’s place within the novel and this adaption places him in a liminal standing: he is at once the reviled and feared outlaw of the stories and yet a man wishing to avoid the trouble set down upon him by his new companion, Chaney. In his war with Cogburn, however, the four-leaf clovers adorning the obsidian-hue handles of his Remington pistols may not have harboured the luck he needed.

[1] https://lithub.com/a-close-reading-of-true-grits-perfect-first-paragraph/

Leave a comment