When I began this collection on the Coen brothers’ work, there was one character who is the anomaly. Inside Llewyn Davis, the Coens’ sixteenth film has always been something of an enigma: the film itself, for instance, often ranks within the pantheon of the brother’s filmography and has yet drawn the ire of some critics for its glacial meander through Greenwich Village, in 1961.

And so, the thought of writing on the film, considering how much has already been written before me, was a challenge that was far easier to shy away from. Not only had the preceding volumes of analysis already shadowed my endeavor, but, also, if included within this collection then would it not be an anomaly itself?

Let me explain.

Principally, as this series is intended to study lesser-celebrated characters from the Coens’ work, the journeyman troubadour Llewyn Davis (portrayed by the masterly Oscar Isaac) typically ranks highly upon the published lists of film critics and journalists. However, while praise has found and remains with the film — the film itself, like its principle balladeer, is ranked by the same outlets as one of the Coens’ finest films: the BBC’s Culture list of the best films of the 21st Century, for instance, placed Inside Llewyn Davis in 11th, a place behind No Country for Old Men, no less — the critical perception of Davis, and while predominantly positive as noted[1][2][3], has often maligned him as cold, grouchy and selfish, to name just three qualities; yet his acerbic nature is evidently a product of grief: having recently lost his fellow-singer Mike Timlin to suicide. Mark Kermode, in his middling review of the film, accurately notes that it remains ambiguous if Davis’s self-centered ways actually drove the young Timlin over the rail of the George Washington Bridge[4]. It’s a morose concept, but one that Llewyn, with his caustic temper, at times makes evidently feasible. Without knowing of Davis’s life before his days as a wandering solo-musician, the film serves as a snapshot, a vignette, of his bid to strike out alone: to us, he is Llewyn Davis, not half of the duo ‘Timlin & Davis’. To us, gone is the cheerful, cardigan-clad partner to Timlin, now Llewyn is off his solo-record, standing within a none-descript doorway alone, framed by the dull concrete-grey of the doorstep and street. This cover, while a mirror of ‘Inside Dave Van Ronk’, is an encapsulation of the isolated Llewyn: the doorway he stands before empty of his partner and his life as a double-act. With this in mind, Inside Llewyn Davis is not only a week-long study of the musical tribulations of a road-bound near burnt-out six-string totting Odysseus, but also one of his grief over the loss of his closest friend. This concept, that the film is a study of loss, is nothing new — in 2013, Sam Adams of Indiewire outlined the perspective — but it is one that is often ignored when the debate surrounding the likeability of Llewyn rises.

Indeed, due to the Coens’ taking inspiration from Dave Van Ronk’s memoir, The Mayor of MacDougal Street, alongside his music, Llewyn Davis is often mistakenly defined as a mirror of Van Ronk, an issue that the musician’s ex-wife and former manager, Terri Thal, has taken with the film:

In the movie, Llewyn Davis is a not-very smart, somewhat selfish, confused young man for whom music is a way to make a living. It’s not a calling, as it was for David and for some others. No one in the film seems to love music.[5]

In this excerpted reading of Davis, however, Thal, after identifying the character’s defining trait of selfishness, questions the integrity at the centre of Davis’s odyssey, a point which the film frequently examines throughout before finally negating at its denouement. If anything, by the conclusion of the film, the only victory that Davis may lay claim to is that his steadfast integrity withstands the beating he has endured. Thal, in her censure of the film, ignores one key point: Llewyn Davis is a composite of several folk-singers, as Ethan Coen delineated to NPR’s Terry Gross:

We were never interested in doing a biopic. That was never the ambition. So the question was we wanted to make a movie about a folk-singer. Who was he? And we did draw on certain aspects of both Van Ronk and other people, like Jack Elliott from the period, New Yorkers who came in from the boroughs and were singing in these basket houses in the Village in 1961.[6]

Not only is Davis, therefore, an amalgam of such musicians, but, through the Coens’ writing, he is also a Coen brothers’ creation, and is, evidently, akin to the characters of their work, and the traits which have defined so many of them. Throughout, Llewyn is berated for his idleness, for his dependency upon others, particularly by Jean Berkey (Carey Mulligan) with vitriolic malice, a friend, in the loosest sense of the term, who loans Llewyn her and her boyfriend Jim’s (Justin Timberlake) couch, as well as, for one regretted fling, her bed. In one subtle, secret moment between the pair, Jean, performing at the Gaslight Cafe alongside Jim and their friend Troy Nelson (Stark Sands), a young soldier with folk-musician aspirations, looks to Llewyn as she sings the winsome 500-Miles, ‘not a shirt on my back, not a penny to my name/ Lord, I can’t go back home this way’, and the parallels soon become evident: Llewyn is lacking in clothes, he is often in need of a ‘winter-coat’; money, a constant need; and a home to actually return to; however, Jean’s dead-glare seems more critical of his lack of shame, her eyes falling upon him with the final line, to which Llewyn simply shrugs at. Beyond their tryst, Jean’s anger at Llewyn is, evidently, linked to his need: a point which the ‘bum’ Jeffery “Dude” Lebowski is also defined and maligned by. Further to his perceived indolence, Llewyn is another of the Coens’ itinerants: from convenience store robbery Herbert I. “Hi” McDunnough (Nicolas Cage), by way of the odyssey of escaped musical-convicts Ulysses Everett McGill (George Clooney), Delmar O’Donnell (Tim Blake Nelson) and Pete (John Turturro), through to the intrepid travails of Mattie Ross (Hailee Steinfeld). It is even possible to see an element of the machinator Tom Reagan (Gabriel Byrne), first, in that both are punched and beaten following some slight, Reagan more so, and also, like Reagan, in that the Coens remain anchored to Llewyn, cutting from him only to present what he is looking at. Indeed, only Miller’s Crossing The Big Lebowski and True Grit may rival Inside Llewyn Davis for its singular, steadfast focus upon its protagonist.

Critically, however, Llewyn, in his travails, is typically linked to Prof. Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg), as Kermode outlines:

While it’s tempting to make comparisons with O Brother, Where Art Thou? (the musical thread seems to bind them together), this is closer in tone to the tested antihero theme of A Serious Man. In that strange little movie, a beleaguered schlub rails against a world that (in his mind) is conspiring to heap hardship and indignity upon him. Llewyn Davis has the same sense of injustice, although his response is not to rail but to ramble, reacting to each new challenge of life by shuffling out of the nearest door, window or fire escape, like a clumsier version of the cat. Both wind up on the streets, but only one of them seems to be there with any sense of purpose.[7]

The idea of Llewyn, the anti-hero, rambling over railing against his plight is evidenced multiple times throughout: anytime that he attempts to address an issue another arises: taking a $200 pay-out on Jim’s ‘Please, Mr. Kennedy’ at the cost of losing any royalties on the song; travelling to Chicago to audition for Mr. Bud Grossman (a taciturn F. Murray Abraham) before rejecting the manager’s offer to join a new three-piece; asking his sister, Joy, to bin some stored oddities without so much as a glance which is then reveled to contain his seaman’s license, prohibiting him from returning to the Merchant Marines; spending $148, all he has, to clear his back-dues, without the license he is then unable to pay the $85 application fee. Any obstacle that presents itself, as Kermode outlines, is ducked only to haunt Llewyn later. In his opportunism and appropriacy, Llewyn’s attention is only towards that which faces him.

It was this opportunism that, for me, defined Llewyn Davis: all of his problems, be it financial or professional, seemingly stem from his obsession with a misguided pragmatism and attention to what is immediately before him. Even when he is asked by Jean, ‘do you ever think about the future at all?’, he may only quip, ‘The future? You mean like flying cars? Hotels on the moon? Tang?’, to which he is concisely told, ‘this is why you’re fucked’. For Jean’s wish to plan ahead, she is remonstrated by Llewyn for being ‘careerist’. Further, the moment that Jean begins to plan for her future, she becomes ‘square’ for her attempt to ‘blueprint the future’, as if, by doing so, she loses her authenticity. In truth, Jean highlights Llewyn’s problem: he is too preoccupied with the past, he is a folk-artist after all, and in his present circumstance that nothing is planned for, everything with Llewyn is reactionary, and it is for this reason that Kermode’s reading of the character is pin-point.

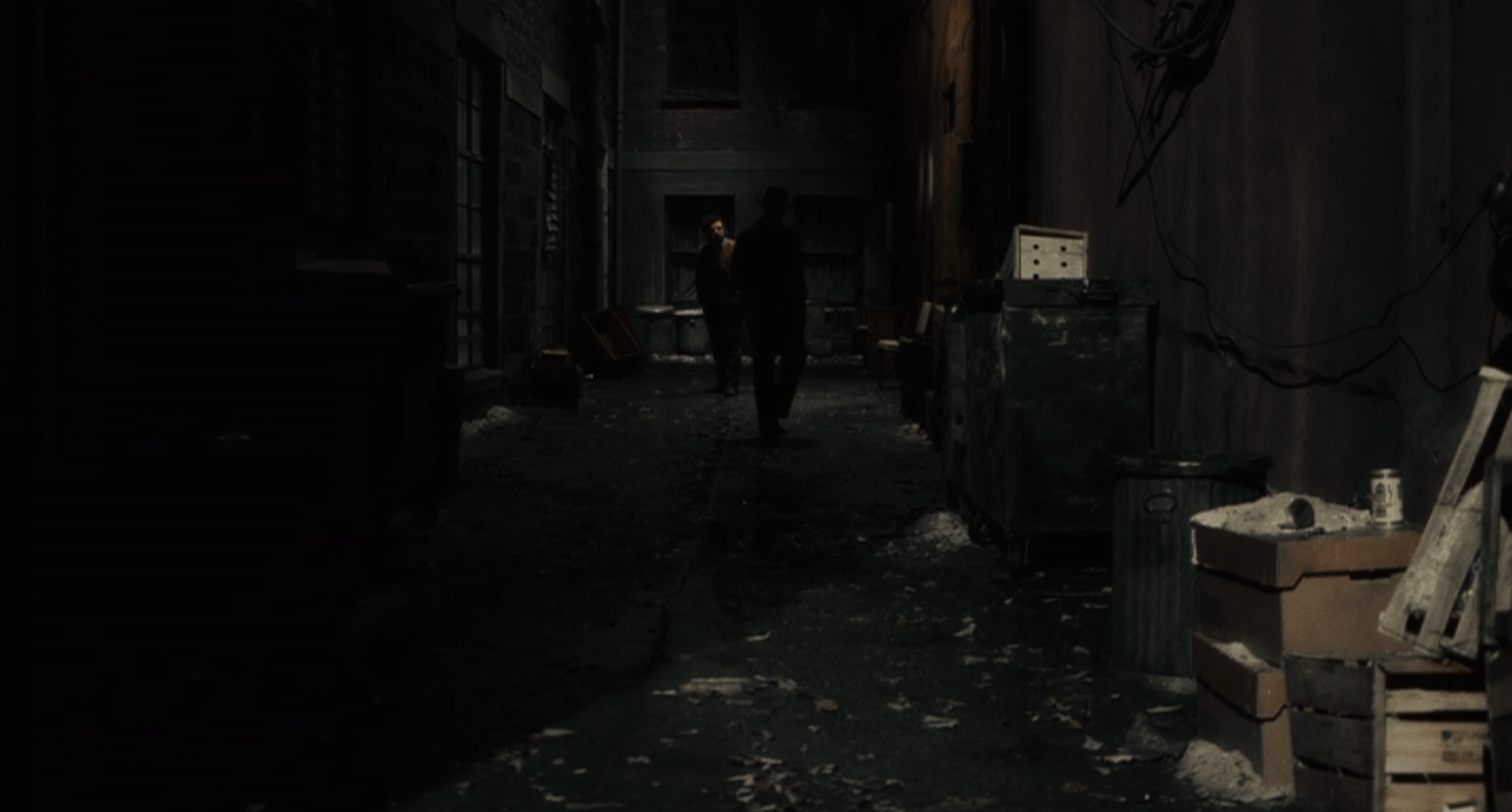

But, Llewyn’s week-long amble is not as rambling as it may first appear: beginning within the dank alley by the Gaslight Café — which the film cyclically returns to at its conclusion — we follow Davis through the Village, before he then hitchhikes to Chicago and Grossman’s Gate of Horn Club for an unsuccessful audition, only to then return to his native New York to once again perform at the café. The circuitous nature of the film implies a stagnation, as if nothing has changed from our first meeting with Llewyn to the final ‘au revoir’; the Coens themselves, in an interview with director Guillermo Del Toro, noted that due to the ‘hamster-wheel’, cyclical structure of the film, it is implied that Llewyn ‘is not going to change. He’s gonna keep on being the same somewhat fucked-up person’[8]. However, Llewyn’s final song indicates a hopeful note for the singer: despite him seeing and literally passing-by the future of folk-music as it takes to the stage and the beating he suffers, he has performed, for the first time, a full rendition of ‘If I had Wings’, the song which he and Mike, as the sleazy Pappi Corsicato (Max Casella) observes, were known for.

However, of his work as a double-act, Llewyn comments, to his distracted agent Mel Novikoff (Jerry Grayson), of the lack of attention ‘Timlin & Davis’ actually received for their debut album, ‘If We Had Wings’, opining that ‘no one knew us [sic] when we were a duo. It’s not like me and Mike were a big act’. Despite the lack of commercial success, the pair’s defining song was that which Llewyn is either unable or unwilling to perform by himself. His reticence is one rooted to Mike, or so it seems.

Throughout the film, ‘If I had Wings’ is performed on two separate instances leading up to Llewyn’s poignant solo performance, and is central to the enigma which the Coens speak of with Del Toro: the first occasion underscores Llewyn travelling through the Village, with cat in arm no less, and is, we presume, off of his and Mike’s record of the same name (Marcus Mumford singing as Timlin); then, during a disastrous dinner with the Gorfeins, Llewyn, after being begged by his hosts and proffered with a Silvertone, begins to sing the song only to immediately halt the performance at the chorus when Lillian Gorfein (Robin Bartlett) attempts a duet, singing ‘Mike’s part’. At the sound of another singer replacing Mike, Llewyn becomes sullen, only to then angrily berate Lillian and Mitch. Already perturbed at having to sing, a ‘trained poodle’ to the other guests, it is Lillian’s mention of Mike’s name which truly riles her guest:

Llewyn Davis: What is that? What are you doing?

Lillian Gorfein: It’s Mike’s part.

Llewyn Davis: Don’t do that!

Lillian Gorfein: It’s Mike’s part.

Llewyn Davis: I know that it is. Don’t do that. Oh, well, you know what, this is bullshit. I’m sorry… I don’t do this, okay? I do this for a living. It’s not a, not a fucking parlour game.

Mitch Gorfein: Llewyn, please, that’s unfair to Lillian.

Llewyn Davis: This is bullshit. I don’t ask you over for dinner and then suggest you give a lecture on the peoples of Meso-America or whatever your pre-Columbian shit is. This is my job. This is how I pay the fucking rent.

Lillian Gorfein: Llewyn, that’s not — this is a loving home.

Llewyn Davis: I’m a fucking professional. And you know what, fuck ‘Mike’s part’!

This scene is a perfect encapsulation of the enigma of Llewyn Davis: his fury at having Mike’s voice, his part, replaced then grows into a defense of his art, his livelihood and then a scathing rejection of his bandmate. Here, the Gorfeins are at a loss as to what causes Llewyn’s anger, with Lillian repeating, in appeasement no less, that the segment of the song she sings is ‘Mike’s’, while Llewyn judges her inclusion to trivialize the song, as if what he does is little more than ‘parlour game’ for his academic hosts to enjoy. Typically, when Mike is mentioned be it by Novikoff, Jean or Corsicato, Llewyn either ushers the conversation along or ignores the mention altogether, as if still grieving or even protective over Mike’s legacy. Here, however, Llewyn’s reaction is one of bitter resentment, one of contempt. In a moment of escalation, the Coens highlight Llewyn’s grief and pique, and how his attitude towards his partner is in equal measure one of loss and rejection. Regardless, however, Llewyn and Mike’s relationship remains ambiguous, but Llewyn’s sense of abandonment is evident when it comes to revisiting ‘If I had Wings’. Indeed, the adage of ‘if it was never new, and it never gets old, then it’s a folk song’ conveys Llewyn’s contradiction, if you will: while evidently reticent to perform the ‘early’ song, it is, ultimately, one he must as its singer, and as a folk-singer at that. If anything, it has become, for those that were aware of ‘Timlin & Davis’, a signature of the pair. Despite the weight of the song for Llewyn, the Gorfeins’ guests simply smile at the prospect of the performance, completely unaware of how the song links to his past alongside Mike. It is a song which Llewyn, despite his efforts to move on, is drawn back to as his trademark.

However, when Llewyn subsequently leaves New York to audition as ‘Llewyn Davis’, a solo artist, he is outrightly rejected by Bud Grossman as ‘no front guy’. In one of the most beautifully concise examples of the cutting nature of the Coens’ character, Grossman, having asked Llewyn to ‘play me {sic} something from ‘Inside Llewyn Davis’ — the sound which implies a more personal song choice — dismantles the notion of Llewyn as anything other than a band-player.

Bud Grossman: I don’t see a lot of money here.

Llewyn Davis: Ok. Ok. So that’s it?

Bud Grossman: You’re ok. You’re not green.

Llewyn Davis: But I don’t have what, say, Troy Nelson has?

Bud Grossman: You know Troy? A good kid. He’s a good kid. Yeah. He connects with people. Look, I’m putting together a trio, two guys and a girl singer. You’re no front guy, but if you cut that down to a goatee, stay out of the sun, you might see how your voice works with the other two. You comfortable with harmonies?

Llewyn Davis: No. Yes. But, um, no. No, I had a partner.

Bud Grossman: Uh-hu. Well, that makes sense. My suggestion? Get back together.

Llewyn Davis: That’s good advice.

Sounding the death-knell of Llewyn’s solo-career, Grossman presents the commerciality factor underlying the decisions to sign a musician to a label. To Grossman, Llewyn is simply ‘ok’, lacking either the talent or the likeability, it remains unclear, that a young musician like Troy Nelson has. The idea of Grossman ‘putting together’, manufacturing a trio, is completely against the wishes of Llewyn. Here, despite the opportunity to be signed as a member of a new group, Llewyn remains loyal to the memory of Mike: his only partner was and will be Mike. Further, the ambiguous notion that Llewyn is ‘not green’ presents a further dilemma for Grossman: Llewyn is seemingly too experienced to be marketed as new commodity: he lacks both the likeability and the aspect to produce a profit.

In truth, the enigma of Llewyn Davis is the great irony, the ‘beautiful contradiction’[9], at the centre of the film: the film itself and the title of his record implying a reflective, open portrayal. Like Del Toro delineates, the Coens ‘never quite go all the way inside’ their protagonist. In response, the Coens draw a parallel to Tom Reagan, the intrigant mobster of Miller’s Crossing, in that both men are a ‘bit of an enigma’, and that, subsequently, both films centre upon discovering ‘who the main guy is’, even if the answer is not forthcoming. It is an irony that is a thread, to varying degrees, which unites the majority of the Coens’ principle characters, as Joel Coen outlined:

‘In the medium of film, you can get enormous power out of characters which are, have a sort of central enigma to them that doesn’t get explained; their power comes from their contradictory impulses […] you don’t want to explain them. You don’t want to ever get the key to them because that’s going to rob the characters of their power, to a certain extent’

This is not to say that the Coens are obtuse, only wishing to reveal, so to speak, their characters to an extent and then no further, but the pair do not wish to explain everything. For the interest to remain, a character must, in some way, be elusive. With the Coens, their characters are defined by opposites: in one instance, an individual may be reflective and confessional and then, in the next moment, deliberately stoic and taciturn; loquacious and then silent; or welcoming and then hostile. It is a conflict, if you will, or a trait which Ethan eludes to as the defining attribute of Llewyn:

“The movie is about how everything’s hard for him. Why is it hard? Is it something in him? Yeah, partly, certainly. At least partly. Wholly? Partly? I dunno […] We wanted a nice dick. We wanted that tension: kind of is, kind of isn’t, kind of is …”

Joel: “He’s the guy who blows his top or speaks out of turn or says something really dickish, but then, three minutes later thinks to himself: I’m a dick for doing that. Some dicks are just not self-aware.”[10]

Behind the vitriolic malice, Llewyn is genuinely sorry for his temper, his outbursts. At the same time, he is his own worst enemy, and at the same time we are then drawn to his plight. In truth, the side of Llewyn that is hidden beneath his anger and his grief is that of his appreciation for what others do for him. After his sojourn to Chicago, a depleted and drained Davis returns to Jean to announce his retirement from folk music. In the same breath, he professes his love for Jean — she having asked Pappi for Llewyn to perform at the Gaslight —, and it seems that, in separating himself from his music, from his role as ‘Llewyn Davis’, can he finally admit the value of his friend and lover. For the first time, the pair share a smile.

Then, Llewyn faces a barrage of challenges: first, he is unable to return the Merchant Marine, not having the $85 to replace his lost seaman’s license. Then, later that evening, he, upon hearing that Jean has slept with the seamy Pappi, belittles and heckles another folk-singer, Elizabeth Hobby. The performer, played by Nancy Blake, is arguably the only ‘genuine folk act that he witnesses’; embittered by Pappi’s boast, Llewyn humiliates Elizabeth: Joel Coen delineates that Llewyn’s attack serves to highlight ‘the examination of what is authentic in terms of the music’ of the folk scene. His drunken heckling is more self-lacerating than it appears: he is, ultimately, depreciating the one thing he has left: his music. His ‘disavowing’ of the folk-scene highlights ‘the contradictions that makes him ambivalent about what he does’, as Ethan outlines. In Davis’s search for authenticity, when he finds an example of it he must push it away from himself, as if he is unwilling to accept that another holds what he searches for. However, what Llewyn’s jeers also evidence is his exhaustion with the folk-scene as a whole: he has performed a seemingly throw-away novelty song for $200; he has been rejected by Grossman on grounds of looks and talent; he has heard Pappi bemoan the poor profits gained from folk-performers at the Gaslight; and now he has heard that Jean has solicited herself so she may perform at the same venue. His outburst, therefore, can also be seen as a rejection of what he has come to see as a fruitless and, ultimately, hollow culture. To many, it is a business. Note also when he is shushed by Hobby’s audience, Llewyn even labels another member of the crowd a ‘fucking phony’, attacking not only the performers of folk-music but also its listeners. In his attack on Hobby, the Coens seem to question what can be authentic about an industry driven by profit? In his loathing, no wonder Llewyn ‘fucking hates folk music’.

Later, however, after returning the Gorfeins like their cat, Ulysses, eventually does, we see how Llewyn has been forgiven for his earlier outburst: the Gorfeins noting that Llewyn’s anger comes from his grief over Mike’s suicide. In an interview with Rolling Stone Magazine, Isaac, in response to a question on the ‘undercurrent of grief […] for his dad, for his partner’, notes:

All those things are inside, right? The grief over that, over his life, over his partner, over where he’s at. But they can’t be overly conscious. You know, it’s there, but you shut that stuff off. When you’re going through hard times you try not to think about it but the weight is on you. And so he’s always walking uphill. If you watch him, no matter which way he’s walking, it’s always uphill. [Laughs.] And then the songs. The songs are the moment. That’s the one moment when you see what he really feels.[11]

Llewyn returns to the Gaslight to finally sing ‘If I had Wings’, the first completely solo-performance he gives of the song. Llewelyn’s final performance of the film is one of acceptance, of moving on. Not until he takes to the stage, following his week-long odyssey alongside and in search of Ulysses the cat, can he bring himself to sing the song. Indeed, while he may remain the same ‘flawed’ ‘fucked-up person’, he has, if nothing else, accepted Mike’s death, having been constantly reminded of his late partner throughout the week. When he steps off of the stage Pappi observes that Llewyn and ‘Mikey use to do that song’, to which Llewyn hardly nods to in response. But Pappi’s point is slightly off. The performance, while acknowledging his past with Mike, also, by way of having actually performing it solo evidences Llewyn’s peace with Mike. A traditional folk-song all the same, but, for the first time, and unlike his performance of ‘The Death of Queen Jane’ for an indifferent Grossman, ‘If I had Wings’ is arguably the only personal song for Llewyn of his discography. The only song which has become his song, and the closest peice of music to an original song for him. Furthermore, the alteration to the plural ‘we’ of the song’s title to the singular ‘I’ pronoun evidences this newly established distance between ‘Timlin & Davis’ and Llewyn himself. By simply performing the song and the amendment to the song’s titular pronoun, Llewyn is no longer shying away from ‘Timlin & Davis’, but rather attempts to claim the song in acknowledgement of Mike and in severance form him: the song presents Davis facing his partner’s death so he can move forward by himself.

As Isaac notes of Llewyn spying the then-unknown Bob Dylan (Ben Pike) as he leaves the Gaslight:

“It’s an amazing shot. For me, one of the most striking things is when Llewyn is going outside and you see that shot of this kid onstage, and there’s these bars from the side of where the seats are that looks like a cell. Like, “That’s not for you!’ [Laughs] “This is not yours.” And yet, and I don’t know how this happens, but I think it comes off as a warm film.”[12]

By the end of the film, Llewyn Davis is still a man out of tune with his surroundings: he is clearly unable to find the commercial success afforded to other performers and yet he is unbending in his pursuit of authenticity. His passing look to Dylan highlights his failure to secure what the young teenager will go onto achieve, but that does not mean that Llewyn has not achieved anything himself. He has grieved the loss of his partner, and will now go on to fully strike out alone, an act that has arguably been hampered by and anchored to his mourning. That loss and his final performance seems more revelatory than what Llewyn’s solo record could ever reveal.

Indeed, from the first time I heard the cryptic ‘au revoir’, it has always remained one of the more perplexing and, for that reason, enthralling closing moments of any Coen brothers’ film, in equal measure for its suddenness and for its apparent aloofness. The call to Hobby’s livid husband, the silhouetted-cowboy stranger having just beaten Llewyn for insulting his wife, may, initially seem random, but the meaning of the farewell is to present the nature of Llewyn Davis himself: he will continue in his ambulatory existence as a folk singer, in that regard nothing has changed: as previously noted, Joel Coen finds that Llewyn acknowledges that Llewyn is not going to change in his pursuit, ‘he’s gonna keep on being the same somewhat fucked-up person’[13] and life will continue to be ‘hard for him’. But, at least he may do so as Llewyn Davis of ‘Inside Llewyn Davis’, rather than as one-half of ‘Timlin & Davis’. In the gutter, as the American folk-scene is about to irreversibly change forever within the building he has propped himself against, Davis remains, arguably for the first time, true to himself, having claimed and hopefully established, by his solo performance of the song, ‘If I had Wings’ as his own. And, as is typical with Llewyn, having just moments before successfully performed his trademark song to an enthralled audience he is then beaten for a past slight. He will go on to achieve more and no doubt then face an obstacle or challenge that will land him back in reality.

On his journey hitching with the garrulous and self-congratulatory jazz-musician Roland Turner (John Goodman) and his taciturn beat-poet valet Johnny-Five (Garrett Hedlund), Llewyn, sat within a toilet cubicle at a roadside-stop, reads scrawled across the cubicle’s tattered wall the searching question, ‘What are you doing?’. It is a simple single shot of the message, to which Llewyn merely glances at, hardly recognising the weight of the question at hand, but there seems to be a deeper reading within reach, even if the question is never deliberately answered or even addressed by its reader. Arguably, one of the more frustrating attributes of Davis is his ability to simply ignore such deeper questions.

Moments like this, such as Mitch Gorfein’s receptionist mishearing Llewyn’s message of ‘Llewyn has the cat’ with ‘Llewyn is the cat’ or the stevedore noting that Davis is ‘not current’, present a deliberate comment on Llewyn himself, but without any further comment by the man himself, and any possibility of further interpretation seems to have been made deliberately opaque by the Coens, as if the question is posed but no answer will be given. It is arguably for this reason that Inside Llewyn Davis never actually gets inside of its titular musician. There is always the lure of discovery without any actually being found. That’s not a criticism, but it may go a way to explain how Llewyn Davis himself has become one of the more complex characters of the Coens’ oeuvre. Even the man himself does not really understand himself.

But, this is only one reading; and I hardly even mentioned the cat.

[1] https://www.vulture.com/article/best-coen-brothers-characters.html

[2] https://www.indiewire.com/2016/02/ranked-the-best-coen-brothers-characters-83984/

[3] https://collider.com/best-coen-brothers-movie-characters/

[4] https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/jan/26/inside-llewyn-davis-review-kermode

[5] https://www.chicagoreader.com/Bleader/archives/2014/01/17/the-folk-song-armys-attack-on-inside-llewyn-davis

[6] https://www.npr.org/transcripts/251638952

[7] https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/jan/26/inside-llewyn-davis-review-kermode

[8] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TaJVm1j_mfA

[9] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TaJVm1j_mfA&t=1465s

[10] https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/jan/16/coen-brothers-inside-llewyn-davis-interview

[11] https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/how-oscar-isaac-became-llewyn-davis-198128/

[12] https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/how-oscar-isaac-became-llewyn-davis-198128/

Leave a comment