‘This will tell the tale’

The Coen brothers’ eighteenth feature film, and their first to be released through Netflix, is comprised of six separate vignettes, each documenting an individual story from the American frontier. It is a Western-anthology film set within a Western-anthology book. Of the six stories, there is a single overarching constant: life within the American West is often unforgivably cruel. Here, in true Coen brothers’ fashion, the landscape, like the landscapes of their previous films — be it any of their films —, is populated by vicious hunters, grasping money-grabbers, and astutely-aware connivers. While hope is prevalent, it is either challenged or dashed entirely, and to keep hope seems to be the greatest hardship of all.

Each of the six stories charts a different course: the opening and eponymous story of the film follows a warbling gunslinger (wonderfully played by Tim Blake-Nelson) who is as equally skilled as an orator as he is with his alternative form of communication: his Colt-revolvers; in Near Algodones an unnamed robber (James Franco) attempts to win big, but is ultimately shown to be unable to win an argument; Meal Ticket, the darkest narrative of the six chapters, tells of the dwindling fortune of a travelling impresario (Liam Neeson) and his spirited performer, Harrison (Harry Melling), a bilateral amputee, whose vigour in his performances of excerpts from literary masterworks is lost upon his audience of impoverished miners; set within the bowl of an Edenic valley, a determined, grizzled prospector (Tom Waits) mines the land of All Gold Canyon for a single nugget of gold, shattering the peace of the untouched paradise forever; the unrelenting and unending terrain of the barren plains is foregrounded in The Gal Who Got Rattled, as the titular ‘gal’, Alice Longabaugh (Zoe Kazan), must face the journey westward in the aftermath of her domineering brother’s (Jefferson Mays) passing; and finally, for the closing chapter of The Mortal Remains, five journeyers — the prudish Lady (Tyne Daly), the reaping bounty-hunters of the Irishman (Brendan Gleeson) and the Englishman (Jonjo O’Neill), the philosophical Frenchman (Saul Rubinek) and the garrulous Trapper (Chelcie Ross) — sit aboard a coach bound for an unknown destination, where they know nothing of what awaits them.

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs is at once replete with ‘Coencentric’ loquaciousness — poetic barbs are as frequently thrown as bullets are fired — and striking silences that echo the loss endured by those who survived the American West. Written over a period of twenty-five years or so, of the six stories four are original compositions – The Ballard of Buster Scruggs, Near Algodones, Meal Ticket and The Mortal Remains — while two are adaptions of short-stories: the first, All Gold Canyon being an exact word-for-word adaption of Jack London’s 1906 short-story, and the second a more revised adaption of Stewart Edward White’s The Girl Who Got Rattled (1901). As noted, The Girl Who Got Rattled follows the Longabaughs after ‘jumping off the map, so to speak’ to journey westward to Oregon for Gilbert’s prospective business ‘associate’, a Mr. Vereen, to meet and then marry his younger sister, Alice. Matthew Dessem’s article for Slate Magazine comments upon how the Coens dramatically altered the tone and characters of the story, and elucidates the disparities between text and film:

For starters, the Coens changed the main character: their version is about Alice and Gilbert Longabaugh (Jefferson Mays and Zoe Kazan) a brother and sister travelling with a wagon train to the Willamette Valley where Gilbert hopes to marry Alice off to a businessman he’s trying to partner up with. Kazan’s character is naïve but not stupid, and over the course of the story, she becomes romantically involved with Billy Knapp (Bill Heck) one of the wagon train’s guides. The short story, which evinces an attitude towards women that could politely be described as “proto-incel,” is instead about the other guide, Alfred — renamed Mr. Arthur (Grainger Hines) in the film — who is ill-at-ease around women, but still manages to find his voice in a crisis. As for the story’s version of Alice, she’s no longer a milquetoast getting pushed around by her brother but “Miss Caldwell”, a spoiled rich kid who has forced her father to send her west to see Deadwood. She’s accompanied by her obnoxious fiancé, a fellow city-slicker, and the couple both delight in teasing and tormenting the tongue-tied Alfred. In other words, it’s about a hypercompetent man who has secret strengths that women don’t appreciate because he is socially awkward, preferring instead to date jerks, and it is structured so that Alfred gets a chance to show off his skills before the woman who has been rude to him receives her comeuppance. There’d be no way to faithfully adapt that to the screen in 2018, so the Coens instead recentered their story on Kazan’s character and turned her from a cartoon into someone with an inner life.

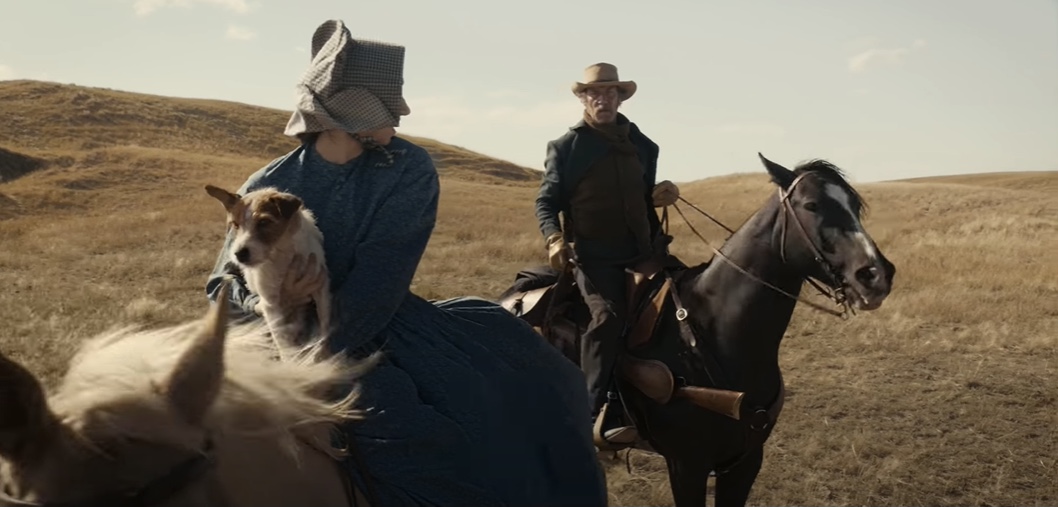

As Dessem’s article notes, the Coens’ adaption of The Gal Who Got Rattled omits the ‘bashful’ and shy wagon-driver of Edward White’s prose, for a reserved and resourceful Mr. Arthur (Grainger Hines). With the Coens, Mr. Arthur’s attention is centred solely upon the journey ahead and the wagon-train behind him. As a character, he is one as uncommunicative with the wagon-party he leads as he is knowledgeable of the land he navigates. But his silence is not a product of his timidity. By definition, Mr. Arthur is, instead, a pragmatist, one who understands the challenges and dangers of charting a course through the prairies enroute to Oregon. And it is this final point, of the sheer fortitude required to journey across the America of the 19th century, that the adaption of the short-story centres upon.

Not long after joining the train, Gilbert succumbs to a suspected bout of cholera, and Alice is left stranded: without money or prospects. Mr. Arthur first appears to give his condolences:

‘Ma’am … Miss? Condolences. Condolences. You going back? You — you going back now or … or …’

In what seems like an echo of the demure Alfred of White’s story, Mr. Arthur stutters through his sympathies to Longabaugh, her kneeling and struck near-silent next to her late brother Gilbert (Jefferson Mays) within her wagon. Sat atop his horse, Mr. Arthur repeats his short ‘condolences’ before shifting to the matter at hand: when is Alice wishing to leave? However, with the arrival of Knapp (Bill Heck), Mr. Arthur’s questions simply trail off, and he sits silently, neither looking to Knapp nor Longabaugh again. He simply stares off. Even as Knapp continues his co-driver’s questions, albeit more tactfully, Mr. Arthur does not interject. So silent is he, he appears not even to listen.

Again, during the burial of Gilbert, he remains atop his horse between Knapp and Longabaugh, by appearance not dismounting to help with either the burial or with the ceremony itself; he only stirs to hightail back toward the train at sound of Knapp’s offer of support to the helpless Longabaugh, leaving the pair alone, his exit dismissive and rude.

Mr. Arthur then remains peripheral to Knapp and Longabaugh’s bashful courting. However, he is frequently foregrounded both by the extolments of Knapp — to him, a ‘top man’ capable and dependable to an almost mythical extent — and then by his brief councils with his co-driver; brief being the optimum word as Mr. Arthur gives hardly a monosyllabic mumble in response to Knapp’s future intentions with Longabaugh. Unlike the source material, the partnership between Mr. Arthur and Knapp is actually central to both characters. In Edward White’s story, Knapp is almost entirely absent from the events of the journey. Neither is he romantically linked to Miss Caldwell nor is he shown to work closely with Mr. Arthur. He is mentioned only three times throughout the story: first as one-half of a ‘tyrannical’ partnership — him being labelled ‘imperturbable’ and ‘thick-skinned’ — and then by Mr. Arthur before he sets off to find the astray Miss Caldwell. Finally, Knapp is noted during the last line of the story, leading the wagon-train. Throughout the adaption, however, the Coen’s foreground Mr. Arthur and Knapp’s team: theirs is a partnership of signals and silences; of navigating and plotting; of pilot and drag; of work and rest. In truth, little do they speak, save for to discuss, or, with Mr. Arthur excusing himself, not to discuss, Longabaugh’s predicament. They work in silence; they eat in silence; and, by the story’s conclusion, are forever bound to remain so.

In two beautifully terse exchanges — in the first, Knapp prospectively outlines his plan propose to Alice, and then, in the second, Knapp discloses Alice’s response — Mr. Arthur hardly gives a word in answer, a grunt to acknowledge his partner’s future intentions. In the first, Knapp’s vague, if not trivial, query of which is ‘worse’, ‘dust or mud’, is languidly answered with ‘both, I guess’. As Knapp discloses his plan to ‘farm’, Mr. Arthur keeps an eye fixed a distant ridge, no opinion on the matter. Evidently, as Knapp may only speak at Mr. Arthur, Mr. Arthur therefore forever remains an enigma — hardly does the inaudible tone of his mumble change at Knapp concluding their enduring partnership — to the man who has ridden ‘pilot and drag’ alongside him for the past twelve years. Knapp, in a simple bid to speak with his partner, is evidently lost as to how to actually approach and speak with him. Again, in the second, Mr. Arthur is more perturbed by his missing hobble, digging within the depths of his saddlebags until the rope is found, than he is hearing Knapp’s news. However, Knapp’s awkwardness is seemingly anchored to his reverence. While his partner is simply irreverent in response! Even the omission of a Christian name — gone is the ‘Alfred’ of the short-story — implies a deference, a formality, that all address Mr. Arthur as such. Be it his co-pilot or a complete stranger.

However, when Mr. Arthur does speak, his words are indicative of his pragmatism: when addressing Alice’s fears over the conniving Matt’s extortionate $400 price for driving the Longabaughs’ wagon, he simply repeats that it is ‘a high-price’, plain as ever; then, when Longabaugh discloses her belief that Gilbert was buried with the pair’s money, he immediately dismisses the idea of returning to exhume the body due to it being a ‘half-day’s ride’ back along the trail. To him, forward is the only option.

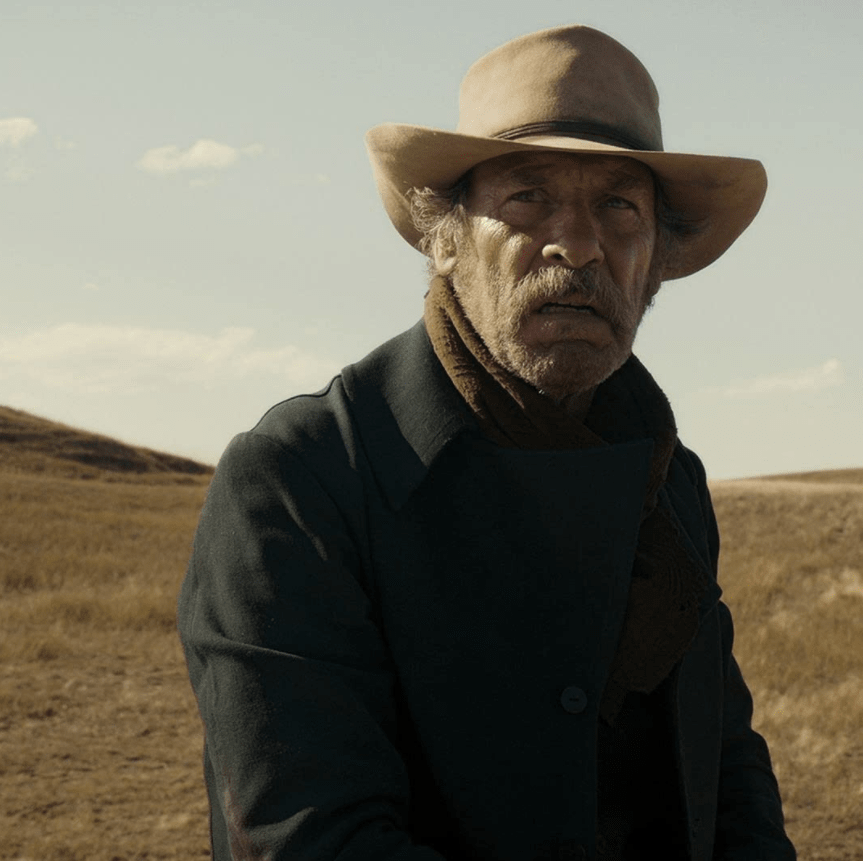

At the beginning of Edward White’s story, the mythology surrounding Mr. Arthur is raised: ‘This is one of the stories of Alfred. There are many of them still floating around the West, for Alfred was in his time very well known’. Such is the way with such tales, the origin of these ‘stories’ are, however, rather ambiguous. Within the opening paragraph alone, Edward White first establishes Alfred’s diminutive height, his apologetic shyness, and his inability to speak with women. In essence, he lacks presence. Then, Edward White delineates Alfred’s adept capabilities as an expert tracker and shooter, able to ‘ride anything’ and ‘shoot accurately’. Lauded as ‘one of the best scouts on the plains.’ It is this latter point, of Alfred’s prowess as an outrider, that the Coens accentuate above all else. If, as Dessem finds, The Girl Who Got Rattled is simply about ‘a hypercompetent man who has secret strengths’, the adaption makes no secret of them. In reference to these ‘stories of Alfred’, the Coens, ignoring the shy attributes of Alfred, delineate the mythical lore surrounding Mr. Arthur principally through Knapp’s veneration:

That man is a wonder. Well, he can read the prairie like a book. To see him cut for sign, well, you’d think the good Lord dealt us each our five senses and bottom dealt Mr Arthur one extra. Still … he is old. I don’t know how it’ll go for him. I can’t help feeling in the wrong.

Rather than snide observations about Alfred’s diminutive height or his frustrating inability to communicate with women, Mr. Arthur’s is known here solely for his peerless skill to read the land. Gone are both his diffidence and his nervousness and in their stead is now an unequalled talent for his navigation of the trail. Heralded as a ‘wonder’, the ‘stories’ of Mr. Arthur are all of his unrivalled experience. Seemingly, the Coens, in rewriting and restructuring the story around the travails of Longabaugh, have kept half of Alfred for Mr. Arthur, and have omitted the multiple discomforts of a man easily embarrassed: for instance, Alfred’s ‘little’ frame — so defining is the adjective that he is known by it — is omitted. With Grainger Hines, Mr. Arthur strikes an imposing presence, and one altogether different to the squat Alfred: coated in a deep-navy woollen jacket, his dark figure, either when on foot or upon horseback, is almost stately. Gone, too, are Alfred’s ‘narrow, sloping shoulders’ as is his ‘pink and white face’: now, Mr. Arthur is hirsute, woolly and moustached, and, from appearance alone, he is a man evidently weathered and hard-worn. And it is this point, of Mr. Arthur’s considerable age, that the Coens anchor Knapp’s outlook of his co-driver to. While fondly regaling Longabaugh of Mr. Arthur’s impressive trail reading, there is also an underlying concern from Knapp: simply, that he may be leaving his partner helpless.

While Edward White notes Alfred’s nickname of ‘sonny’, the Coens cast Mr. Arthur as a remnant of a lost age, and is shown to be, to borrow from Charles Portis, a man of ‘true grit’. Knapp’s repeated mention of Mr. Arthur’s ‘old’ age can be interpreted in two ways: the first, in that Alice Longabaugh gives Knapp a chance to leave the trail. While his proposal of marriage is one offered in complete ‘respect’, he, too, is aware of what his life is to be if he remains a guide: ‘looking’ at Mr. Arthur, Knapp’s future is one of ‘no family’ and of sleeping rough, of ceaseless toil and hard living. He will continue life without a family, and he will, like his partner, remain alone and solely committed to the trail. To Knapp, Mr. Arthur’s way of life is unsustainable, and, more importantly, undesirable. If he remains a guide, over time, Knapp will inevitably become like Mr. Arthur: save for the trail, he will have nothing. Under the Homestead Act, however, Knapp and Longabaugh will be entitled to 640 acres: in the years guiding the trail to Oregon, Knapp, unlike his co-driver, now sees a future at the end of it. For Knapp, marriage is not only a means to aid Alice Longabaugh in her predicament. A life of transit is undercut by a life of settlement.

Secondly, Knapp’s refrain is also indicative of one of the film’s central themes: that of the passing of time, of change. In Knapp’s guilt, he fears that Mr. Arthur’s own future is uncertain. While he attempts to assure his partner that he ‘will do fine solo’, Knapp privately lacks such conviction. Despite Knapp’s awe at Mr. Arthur, there is an underlying sense that perhaps his time has passed. That he is too old for such hard-work. It is a concern of Knapp’s that is quickly countered by Longabaugh, that his ‘first responsibility is to [his] household’. And the subject is left. Knapp’s attention is instead drawn to his own future, rather than to that of his partner’s and the issue of Mr. Arthur’s age is undecided, until vignette’s conclusion.

However, despite Knapp’s concerns, the Coens intermittently foreshadow the adept skills of Mr. Arthur: first, as Knapp fails to shoot the yapping President Pierce, he bemoans that he ‘should have deputised Mr. Arthur. That man is a crack-shot’; then, Knapp, in his attempt to speak with Mr. Arthur, highlights the value placed upon his ‘skills’, and that he ‘will do fine solo’ as a result; and, finally, in a quote lifted directly from Edward White, Knapp praises his partner’s ability to ‘read the prairie like a book’. If anything, the final confrontation with the Sioux war-tribe is simply a coalescence and confirmation of these observations; however, while Alfred’s stand against the war-party serves to show his true-self, his hidden proficiency as a scout, Mr. Arthur, unbeknownst to him, proves that his age is, ultimately, of little consequence: experience wins the day.

Ultimately, while the adaption has been accurately defined as a ‘story about nerve’[1], it is also one which is tethered to communication, of how people understand one another. Between the triptych of Knapp, Longabaugh and Mr. Arthur The Gal Who Got Rattled is a study of how these three uniquely different people co-exist within an egalitarian land not fully understood. With Alice Longabaugh the Coens find their innocent, their fresh-eyes to the landscape. Unlike her counterpart, Miss Caldwell, Alice Longabaugh is neither cruel nor arrogant. Nor is she journeying upon the whim of an equally obnoxious fiancé, but is rather forced onto and then along the Oregon Trail due to a scheme of her self-righteous brother: she is to wed a Mr. Vereen. Longabaugh is timid, but kind, and, while struck stranded, she manages to face the journey west with a stoic determination. Despite having to initially endure the idiocy of her brother’s business venture — his grand scheme of using his sister to secure his own partnership — she continues stoically along, under the ever-watchful eye of Knapp.

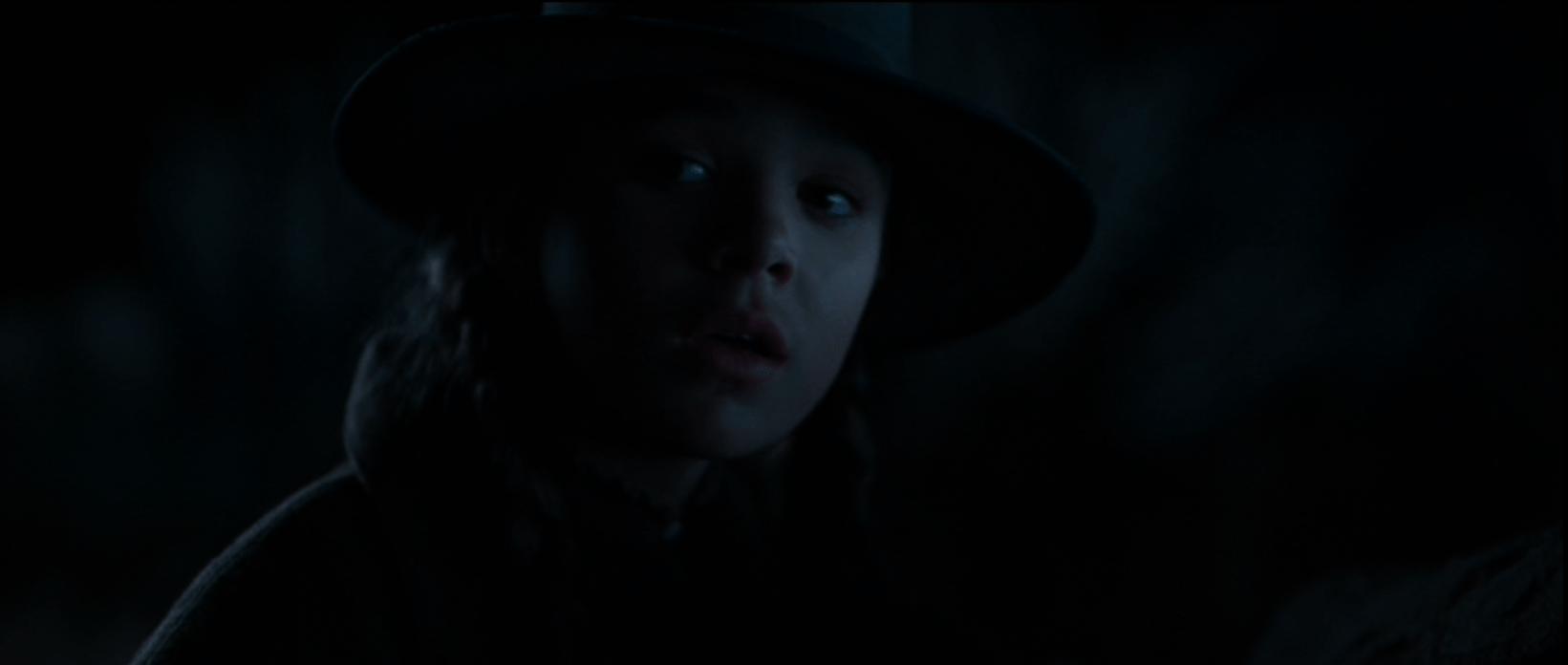

Longabaugh and Knapp’s final conversation, in which the former discloses that her brother would scold her for being uncertain, ‘wishy washy’ in her beliefs, is entwinned with a twisted irony. To begin with, Knapp’s support for Longabaugh, noting that ‘certainty is the easy path’, challenges the once dominant voice of the late Gilbert; his beliefs were, clearly, steadfast and stubbornly fixed: in this moment, of Knapp supporting Alice, the pair are united, with Knapp going on to finish Alice’s beginning of Matthew 7:14, ‘straight is the gate … and narrow the way’. Here, the pair seem to enjoy the notion that to break from the ‘narrow’ path for uncertain pastures is to be embraced, not shunned. That ‘certainty’ avoids the spontaneity of life. For the pair, only in death there is certainty; to Knapp, ‘uncertainty […] is appropriate for matters of this world’. Sitting opposite one another over a camp fire, the couple are wishing to start anew; to break from their pasts and begin again. However, despite her burgeoning love and adoration for Billy Knapp, Longabaugh underestimates one simple instruction: ‘best not to get too far from the train’. The following morning, Longabaugh quite literally leaves the ‘path’, the trail, to find the missing President Pierce. It is a bitter, twisted irony that, only the night before the pair were relishing the uncertainty of what’s ahead, Longabaugh, naively, wanders away from the safety of the train and into a land so unpredictable and wild. Uncertainty and spontaneity with love is one thing; uncertainty travelling the plains is fatal, and Longabaugh, unheeding Knapp’s earlier advice, unwittingly dooms herself.

Enter Mr. Arthur.

In the most faithful sequence of the adaption, Mr. Arthur is then shown reading ‘sign’ of an unseen war-tribe. The muddied footprints surrounding a small puddle gives him what he needs: sign of others. Here, Mr. Arthur, in response to one of the train’s outriders enquiring of his findings, simply states that there is sign of ‘horses’, and orders the wagons to ‘keep on’ while he’s ‘gonna talk to Mr. Knapp’. Sign of horses is enough. There is no need to say more. It is a moment strikingly referenced to Alfred’s searching:

On a bare spot of the prairie he discerned the print of a hoof. It was not that of one of the train’s animals. Alfred knew this, because just to one side of it, caught under a grass-blade so cunningly that only the little scout’s eyes could have discerned it at all, was a single blue bead. Alfred rode out on the prairie to right and left, and found the hoof-prints of about thirty ponies. He pushed his hat back and wrinkled his brow, for the one thing he was looking for he could not find–the two narrow furrows made by the ends of teepee-poles dragging along on either side of the ponies. The absence of these indicated that the band was composed entirely of bucks, and bucks were likely to mean mischief.

Within the adaption, Mr. Arthur, alone, looks off to the distance, as he typically does; ever cautiously watchful for what is ahead. He knows what is nearby, even if there has been no sign of any tribe before this: here, Knapp’s previous instruction to Longabaugh to keep close to the train is now shown to not only be due to the fact that she might ‘get lost’. With this busy site, now we see the ominous trace of who else navigates the plains. Returning to the train, he quickly departs again in search of Longabaugh — directed by the dubious Matt that she went ‘over there’, nodding off towards a rise close-by; again, the Coens lift directly from the page:

He followed Miss Caldwell’s trail quite rapidly, for the trail was fresh. As long as he looked intently for hoof-marks, nothing was to be seen, the prairie was apparently virgin; but by glancing the eye forty or fifty yards ahead, a faint line was discernible through the grasses. Alfred came upon Miss Caldwell seated quietly on her horse in the very centre of a prairie-dog town, and so, of course, in the midst of an area of comparatively desert character. She was amusing herself by watching the marmots as they barked, or watched, or peeped at her, according to their distance from her.

As he arrives beside Longabaugh, Mr. Arthur’s uneasiness is even more evident. Conveyed through a ‘shot reverse-shot’, the Coens perfectly frame the severe contrast between the innocent Longabaugh and the anxious Mr. Arthur. While typically utilised to create a ‘sense of presence’, as their frequent collaborator Roger Deakins imparts, during a conversation between two characters: here, it concisely displays how oblivious Longabaugh is. And it is from here, of how, between them, there is no clear line of communication, that the severity of the danger is presented: one is joyfully laughing while the other is panicked. Like Zoe Kazan finds, Longabaugh ‘was like a bird in a cage’ who is suddenly freed and begins to feel ‘the air on her feathers’[2], but is, as a result, entirely unaware of the world around her; with President Pierce alongside her, barking at prairie dogs, she is jovial, and entirely clueless to the danger she has unwittingly placed herself in.

Once the camera returns to Mr. Arthur his scanning eyes are suddenly fixed-off into the far distance, his aspect awash with fear. Here, for the first time, the camera is intensely close and tight upon Hines. Typically, Hines is framed either before or within the vista of the plains in a medium-long shot. The hills forever receding into the blue. Having followed Mr. Arthur’s tracking of Longabaugh from a distance, him being, at times, little more than a speck within an extreme wide shot, the moment in which Mr. Arthur catches first sight of the lone rider is confined and cramped. Now, by transitioning to a single wide-shot of Mr. Arthur, it is clear that the pair are unescapably cornered, even before the riders have instigated any charge. Regardless of the unending expanse surrounding them, the pair are nevertheless trapped. Hines silently conveys the sheer panic of the sight: finally materialised before Mr. Arthur sits the ‘mucky-muck’ of the party, silhouetted stark against the sky, who is then joined by the rest of his tribe: near on twenty riders. From a wordless look, Mr. Arthur appears, for a fleeting instance, rattled himself.

With a start, Mr. Arthur is at once down from his horse to pull Longabaugh off her mount, ordering her to find cover behind a nearby rise. After Mr. Arthur’s proffer of peace to the outrider is ignored, he immediately sets to hobbling and unsaddling both horses, preparing to stand against the rush of the tribe. As he works, he precisely outlines the exact course the party will take. Almost as if he is plotting their course himself! While Alice Longabaugh stands wheeling around in search of either more riders or of escape, Mr. Arthur gathers his meagre armaments: two Colt revolvers and a Henry 1860 rifle. While Longabaugh sees only ‘one savage’, Mr. Arthur gives a short cackle at such an innocent assertion, and, at the moment he instructs her to ‘keep lookin’, the rider is immediately joined by more. Evidently, so calm is he, Mr. Arthur can read his enemy as adroitly as the lands he navigates:

It’s a war-party and we probably look like easy-pickin’s. What they’ll do, they’ll rush us. Course, dog-holes as bad fer them as fer us, and they don’t know how to fight. If they was to come in on all sides I couldn’t handle ‘em, but they rush in a bunch, like damn fools! I beg your pardon, Miss. Now you keep low here. (Handing her his Colt Open Top) Take this. Take it. Take it now. Got two bullets in it. It ain’t for shooting Indians. If I see we’re licked, I’m gonna shoot you and then I’m gonna shoot myself, so that’s okay. But if you see that I’m done for, well, you’re gonna have to do for yourself. Now you put it right there so’s you can’t miss. […] This is business, Miss. Longabaugh. If they catch you, it won’t be so good. After they take off every stitch of your clothes and have their way with you, they’ll stretch you out with a rawhide, and then they’ll drive a stake through the middle of your body into the ground, and then they’ll do some other things. And we can’t have that. Now, we ain’t licked yet. But if we are, you know what to do.

Here, this monologue, and while almost verbatim of Edward White’s prose, is not the point at which Mr. Arthur, unlike Alfred, strides forward assertively in an act of brilliant confidence, awing the childish ‘girl’. Nor is it the point where all preconceived notions of a tongue-tied plainsman are completely dashed. It is not used to portray the ignorance of a young, haughty woman and nor does it stand to rebuff the arrogance of such ‘lady sorts.’ Edward White’s scene is one of Alfred showing the impertinent Miss. Caldwell how capable he actually is. At once, Alfred’s stutter is completely overcome. No longer is Alfred the ‘queerest little fellow’ of ridicule. Instead, he is powerfully assertive when facing a danger that only he, and his kind of ‘plainsman’, can handle. A danger that the confident city-types of Miss. Caldwell are woefully unprepared for. In truth, the portrayal of Miss. Caldwell is partly a scathing critique of a greenhorn, ignorant of the wilderness of America.

For The Gal Who Got Rattled, on the other hand, the stand is not to show how Mr. Arthur has been foolishly misunderstood, nor is it a phoenixlike rebirth before a bully, but rather, for the Coens, it conveys how the grand rumours and tales of his talents are entirely true. So far, all we have as measure of the man is Knapp’s high praise: from leaving the train to the final bullet, Mr. Arthur’s scouting, tracking and marksmanship are all fully revealed. As is his knowledge of the terrain; knowledge he quickly attempts to impart. It is an education that overwhelms Longabaugh entirely. His offer of the Colt Open Top is rejected, understandably, with a repeating terror-stricken ‘no’. But Mr. Arthur’s blunt response of ‘this is business, Miss. Longabaugh’ is a perfect counter to the ‘business’ what set the Longabaughs upon their journey west: after all, the siblings were, originally, travelling to Oregon for Gilbert’s ‘business opportunity’. For Mr. Arthur, ‘business’ is the sort which is managed by such a ‘fight.’ ‘Business’ along the plains is a simple matter of survival. It is necessary, and what is to be expected! Unlike the vague ‘business opportunity’ of the Longabaughs, which, by all measure, was so uncertain that their entire journey commences because of a wish and whim. Essentially, ‘business’ for Mr. Arthur is what has to be done, rather than what is hoped for. And in his telling of the Siouxs’ methods, Longabaugh learns more from him than she ever did her feckless brother. Mr. Arthur’s unperturbed nature has been anchored to a fact: his readiness and stoicism is grounded by his experience; he is confidant because he has endured. He is readily equipped for any eventuality and he communicates this, plain and true, to his terrified charge.

The syndetic listing, for instance, of what tortures await Longabaugh if the war-party ‘catch’ her is the moment in which the true desperation of their predicament is fully realised by her: Mr. Arthur’s successive inclusion of ‘and’ here concisely clarifies how long and barbaric a process her death will be. This step-by-step sequencing of his telling is so precise and exact that it is evident that Mr. Arthur has witnessed the aftermath of such a slaughter. However, despite prospectively depicting her rape and torture, the final part of her killing is left ominously non-descript: the equivocal ‘things’ he alludes to is seemingly so severe that Mr. Arthur does not wish to say more, and nor does he need to: from then on, Alice Longabaugh knowns ‘what to do’. For the first time, since he handed her a pistol, Longabaugh understands the situation, and, more importantly, what her part is within it.

Mr. Arthur is not apologetic in his delivery, save for his excusing himself for cussing ‘damn’ to Longabaugh. Alfred, maligning the Sioux as ‘damn fools’ ‘blushes’ and apologises ‘abjectly’ and ‘profusely’. Mr Arthur, however, is far more comforting to Longabaugh. Once Alfred commences to battling the war-party, his attention is only towards his enemy, relishing the opportunity; he even has a new ‘shine’ to eyes. With Mr. Arthur, throughout he regularly addresses Longabaugh: in the first instance, he identifies that the tribe begin firing their guns to ‘scare’ the pair; he then rhetorically asserts, ‘won’t bother us none, will it, Miss?’. Which the cowering Longabaugh quickly concurs: ‘No, Mr. Arthur’. Later, after the tribe retreats, Mr. Arthur asks Longabaugh if ‘she is alright’, to which Longabaugh shakily responds with ‘yes, Mr. Arthur’. His matter-of-fact manner is underlined by a gentle politeness. Despite him initially appearing ignorant of Alice Longabaugh whenever she met with Knapp, here, his priority is her safety. He acknowledges that the pair are in for a ‘good fight’, but this is not a relishing of the occasion. Unlike Alfred, who finds such an occasion ‘good’, Mr. Arthur is far more reserved. To Mr. Arthur, the ‘good fight’ he refers to is more to the challenge of it, rather than for the joy of what’s to come.

The second charge is deemed to be the deciding battle: moving away from the safety of the rise, Mr. Arthur stands in full sight of the charge in order to get a clear bead upon the party’s leader. It is here, having loaded and cocked his rifle, that he utters the phrase that has come to define the nature of the collection: ‘This will tell the tale’. The adage, a summary of the life and death battle, fittingly encapsulates what the fight is: two almost mythical sides of the west clashing together. The lone ‘plainsman’ and the vanishing Native tribes. To ‘tell the tale’, so to speak, is exactly what Edward White alludes to at the beginning of his story: this stand, and instances like it, have come to define the ‘stories’ of Alfred and Mr. Arthur alike, and why, in our case, Mr. Arthur is placed in a position of such high-regard and veneration. Indeed, Mr. Arthur’s actions, and the retelling of them, are similar to those tales of Rooster Cogburn. Within True Grit, as Cogburn (Jeff Bridges) and Mattie Ross (Hailee Steinfeld) await the arrival of the Ned Pepper Gang, the old marshal regales his young charge with a story of himself:

Rooster: It is just a turkey shoot. There was one time in New Mexico, when Bo was a strong colt and I myself had less tarnish, we was being pursued by seven men. I turned Bo around and taken the reins in my teeth and rode right at them boys firing them two navy sixes I carry on my saddle. Well I guess they was all married men who loved their families as they scattered and run for home.

Mattie: That is hard to believe.

Rooster: What is?

Mattie: One man riding at seven.

Rooster: It is true enough. You go for a man hard enough and fast enough and he don’t have time to think about how many is with him—he thinks about himself and how he may get clear of the wrath that is about to set down on him.

Connections between True Grit and The Ballad of Buster Scruggs are evident: a sign for ‘Greaser Bob’s’ is mentioned within Meal Ticket; within The Gal Who Got Rattled Grandma Turner is present again; and, finally, for Mortal Remains, the tale of the ‘Midnight Caller’ is once again not told. However, between Mr. Arthur’s stand and Cogburn’s seemingly incredulous charge, both men are defined by their legend. What may seem insurmountable to most, these men will face any challenge, and, with both, their actions later confirm the validity of such grand ‘stories’. However, while Cogburn is happy to discuss his tale of derring-do, Mr. Arthur gives no word to his own. Save for Billy Knapp’s observations and stories, Mr. Arthur’s achievements would not be known, so reserved is he.

Finally, Mr. Arthur’s killing of the last-standing Sioux both saves and dooms Longabaugh. In confusion, and in following Mr. Arthur’s imperative of ‘just do as I say’, she shoots herself believing Mr. Arthur has been killed. His grief reduces him to silence. Indeed, while The Girl Who Got Rattled concludes with Alfred executing three surviving Sioux warriors, the Coens take a more mournful approach. Having covered Alice Longabaugh with his coat, he gathers his hat and armaments and sets off in search of the wagon-train. As he departs with President Pierce, he executes one struggling warrior. Written upon the final page of the story of The Gal Who Got Rattled, Mr. Arthur, looks for ‘no landmark’, and keeps his ‘eyes downcast. His aspect ‘grim’. Indeed, Mr. Arthur’s silence is one of complete loss. In his mastery of navigating the plains, he negates one simple fact: the fear of Alice Longabaugh. She did as instructed. And this is the true tragedy of her fate.

Mr. Arthur had no idea what to say to Billy Knapp’, is, seemingly, in part an acknowledgment to his tongue-tied counter-part, Alfred. But here, rather than being rooted in a social-awkwardness like Alfred, Mr. Arthur’s silence is instead tethered to his grief. Mr. Arthur’s dejection is clear: his defeated conclusion, that the ‘poor little gal […] hadn’t ought to have did it’, is tragically clipped. So ‘rattled’ is he that he cannot recount the circumstances of her fate. Ultimately, he cannot actually ‘tell the tale’ of what has happened. In truth, the notion of stories is ultimately the principle theme of the collection, and is one which frequently appears throughout the Coens oeuvre. With The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, the titular outlaw is constantly redefining the sobriquets attributed to him; in NearAlgodones the unnamed robber attempts to become an outlaw and fails miserably; for Meal Ticket, the Impresario and the Artist monetise the dramatic telling of prose and poetry; All Gold Canyon, with its setting, looks to be the landscape of almost mythical and fabled beauty; and, finally, The Mortal Remains features five storytellers, each with their own reflections upon their lives. With the final stand of The Gal Who Got Rattled, the tales of Mr. Arthur’s abilities are validated. Yet, unlike the self-aggrandising Buster Scruggs or the sometimes garrulous Cogburn, Mr. Arthur, while as equipped as both, gives no word to his legend. Despite what he as just survived, the only thought he can give attention to is to the death of Alice Longabaugh, and to what he cannot say to her love.

Save for the words written within the collection of The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, this story would be one lost. Seemingly, the telling of the tale will have to fall to someone else. Mr. Arthur is, uncharacteristically, too rattled to speak.

(There is a larger discussion here in the peripheral, fleeting portrayal of the Native Americans within the six-stories of The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Only twice do they appear, and in both occasions for the same purpose: to maraud and kill. This simplistic portrayal, Alice Longabaugh even labels the lone Indian scout as a ‘savage’, has incurred the ere of critics. Articles relating to the argument have been linked below. For the purpose of this article, the analysis of the segment has centred solely upon Mr. Arthur and his battle with the Sioux has been discussed from this standpoint. I do not feel qualified to discuss the portrayal of the Sioux, when Native Americans themselves have given a far more educated judgement upon the piece. This is not a short-changing of the issue nor is it intended to diminish the importance of the conversation)

[1] https://medium.com/movie-deep-dives/a-conversation-with-the-ballad-of-buster-scruggs-pt-5-the-gal-who-got-rattled-68f602c39ec1

[2] https://www.vulture.com/2018/11/zoe-kazan-on-being-vulnerable-in-buster-scruggs.html

Leave a comment