Soldiering: The Subject of War within Sebastian Barry’s A Long Long Way

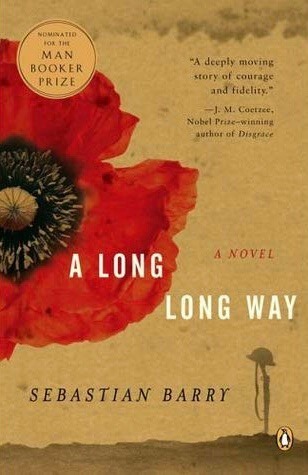

Sebastian Barry’s fifth novel, A Long Long Way, centres upon the brief life of Private William ‘Willie’ Dunne, an apprentice builder from County Wicklow whose experiences as a recruit in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers portrays the abject horror of trench-warfare during World War I; the socio-political divisions within Ireland at the time over the prospect of Home-Rule, from 1914-1918; and how an individual may attempt to preserve their humanity in the presence of incessant and unceasing conflict. This article, the first of two prospective essays upon the subject of war within Barry’s literature, will take the form of a character profile of William Dunne, and how the novel’s protagonist is shaped by his experiences during the war, from the yellow haze of Flanders to his rest-bite sojourn to the quiet homestead of the deceased Captain Pasley, within Tinahely, County Wicklow (253).

Barry’s portrayal of the life of a soldier is also evident within his latest novel, Days Without End (2016), in which the Sligo-born Thomas McNulty endeavours to form a life within an America beset by war. Days Without End serves, while not directly, as something of a companion piece to A Long Long Way: seemingly unconnected, a uniting principle ties the two solders together: their search for domesticity in a life unequivocally altered by war. In order to analyse the novels’ prose, the ordering of the essays will follow the chronology of Barry’s publications, as opposed to the narrative timeline of the two families at the centre of Barry’s fiction: the Dunnes and the McNultys. Ultimately, however, Barry’s prose will be analysed, specifically his depictions of conflict and violence, with particular attention given to detailing both Dunne and McNulty’s altered and disparate attitudes towards their situations within war

For Dunne, and while the reasons for an Irishman’s enlistment within the war effort are noted by Barry for their complexity — decisions are based upon familial attitudes relating to either the hope of or the objection to Ireland’s Home Rule— his voluntary joining of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers is rooted by an issue of self-confidence and insecurity pertaining to his ‘damnable’ height (6). From the age of sixteen, his perceived meek stature produces a shame that comes to shape his existence, with his inability to follow in his father’s footsteps and join the Dublin Metropolitan Police, or the DMP, as abbreviated, attributed to being below ‘the regulation height for a recruit’ (6) at five foot, six inches. Here, Barry reduces the impetus for Dunne’s decision to enlist to a single truth: ‘For if he could not be a policeman, he could be a soldier’ (15). While many soldiers, like the ferociously tempered Private Jesse Kirwan, for instance, are embittered and divided over Irish republicanism and unionism, Dunne is naïve to such political leanings. To him, volunteering, regardless of intent or motivation, is void by the war. For Dunne, survival is the objective to any man’s cause.

Travelling from the training depot in Fermoy, County Cork, to the North Wall in Dublin, the Fusiliers then travel through England and France before reaching Flanders; it is here, within the scared fields of Belgium, where Dunne endures his first instances of trench warfare. Under the leadership of the peaceable Captain Pasley, from Tinahely, a devoted son and heir to his family’s farm, the regiment is decimated by their exposure to a ‘big snake’ of yellow smoke, drifting towards them in their innocence. With the novel itself predominantly narrated from a subjective third-person perspective, Barry’s portrayal of violence is taken from what Dunne witnesses, and so is visceral and unrelenting. For instance, the aftermath of a gas-attack, the first point of warfare within the novel, leaves an indelible mark upon Dunne, as, looking into the trench, the sight of his fallen friends is drawn to an antic scene of empirical collapse and ruin:

The hole was filled with bodies, and to him they looked like dozens and dozens of garden statues of the sort you might see in Humewood, where his grandfather had worked, fallen down like figures from some vanished empire, thinkers, and senators and poets unknown, with their hands raised in impressive attitudes, their stone bodies for some reason half clothed in the uniforms of this modern war. The faces were contorted like devils’ in a book of admonition, like the faces of the truly fallen, the damned, and the condemned. Horrible dreams hung in their faces as if the foulest nightmares had gripped them and remained visible now frozen in direst death. Their mouths were ringed and caked with greeny slime, as if they were the poor Irish cottagers of old, who people said in the last extremity of hunger had eaten of the very nettles in the fields. And still the echo, foul in itself, of that ferocious stench hanging everywhere [30]

Within Chapter Sixteen of the novel, Father Buckley, the exhausted priest of the regiment, recounts the life of a deceased soldier’s mother. To Dunne, the story ‘sounded like a fable’ (162) for its fantastical and exaggerated telling. The critique, however, while negative to Dunne, is, conversely, a positive attribute of Barry’s prose. At times, Barry conveys the war as though a scene from a storybook or a fable, not to conceal the truth of the matter, but, rather, to detail the horror of a scene. Of the extract, excerpted from Chapter Three, for instance, the remains of the soldiers are forever ‘frozen’ within Dunne’s consciousness, preserved within the horror of their suffocation. However, Barry’s distillation of the scene is one rooted within the past of a bygone, undermined age and is so foreign to Dunne that he stands stilled by the sight, despite having survived the self-same attack himself. Here, Barry is almost Miltonic in his presentation of the dead: in their ‘fallen’ states, bequeathed the comparison to the ‘truly damned’ of the Underworld, the men resemble more the exiled angels of Heaven, ‘outcast of God’ and those ‘condemned to wasted eternal days in woe and pain’[1], as is noted within Book II of Milton’s epic, Paradise Lost (1667). Barry’s haunting evocation of the aftermath of the mustard-gas attack is not grandiose, but rather a study of an event which appears to have no firm holding within history: nothing has been seen by either Dunne or his fellow soldiers at this stage of the War, and so is seemingly incomprehensible. In truth, other than the ‘greeny slime’ coating the soldiers, the bodies of the men evidence only a calamity, rather than a particular event. The corpses depict a struggle, but the cause of their deaths seems, with the smoke’s dissipation, unclear. It is beyond Dunne, who can now find no evidence of the cause of their deaths, other than the lingering ‘stench’ (30) of the gas. It is a form of warfare unlike any other: traceless and yet devastating, and Barry conveys the desolation through the epicism of biblical allegory. Unlike Father Buckley’s fabled telling of a tale, Barry detailing of the dead and their communal grave reads as a ‘truthful’, forbidding account.

Beyond the bodies resembling the artefacts of ‘some vanquished empire’, with the corpses as effigies, appearing as though long dead ‘thinkers’, ‘senators’, and ‘poets’, Barry brings the tableaux of the fallen soldiers back to a present forms of history relatable to Dunne. Firstly, Dunne’s childhood memory is distilled in the recalling of the ‘garden statues of the sort you might see in Humewood, where his grandfather worked’; he may only draw from what he knows. Building upon this grounding, Barry, by the end of the paragraph, has expanded his scope to the Irish famine. While preceding the events of the novel by almost seventy years, by the brief reference to the dead mirroring the reduced states of the soldiers’ antecedents, Barry tethers the novel to a known history, one easily recalled by the Irishmen whom he is portraying. By this fleeting reference, the war is at once personal and ancient, respectively, to Dunne, whose service is replete with such moments that the young Irishman is both surviving his present whilst be drawn into the past sufferings of his own country and beyond. In a single line, Barry adroitly establishes the context of Dunne’s survival: with his forefathers having survived one form of hardship, he must now fight within a war of attrition. Another generation of Irish having suffered one after the other; the ‘echo’ here is not just of the gas, but also of the sights recorded within an Irish history. Ultimately, in order to convey the horror of this modern form of warfare, presently unseen by the soldiers of the frontline, Barry mines the annals of history, binding parallels between ancient skirmishes, akin to Milton’s fallen angels, and the trench-warfare which furrowed the fields of 20th century Europe: the coalescing of the past and present, ancient and modern, produces a terrifying new form of war endured by such innocent men as Willie Dunne.

From the excerpted lines alone, one notable attribute of Barry’s literature is that of his use of analogy, his prose being often replete with figurative language: within the trench, the dead are ‘like dozens and dozens of garden statues’, their bodies now turned to ‘stone’ in their stillness, and bearing a resemblance to the starved Irish of the famine. With a penchant for utilising such similes and metaphors, alongside personification, Barry is consciously drawing a scene to that of another reminiscence or event, whether past or present, respectively, and A Long Long Way, like the rest of his oeuvre, is beautifully laced with such instances. During the Easter Rising, with the Irish soldiers ordered to quell a Republican insurrection, Barry labels the dragoons’ appearance of that akin to the ‘old Greeks’ (87) in a scene reminiscent of ‘heroic figures in a vast painting’ (87). With these fleeting moments, there is a classical rendering of war as though the streets of Dublin resemble, for a moment, the epic narratives of the ancient world. Effectively, Barry’s initial distillation, transitory in its tether to a point within history, then gives way for the violence of the battle to remove the classical quality of such moments. There is beauty within the Grecian tie to war here, but such analogies also perfectly convey the brutality of what is facing these soldiers. Such analogies momentarily elevate the narrative from the squalid surroundings endured by Dunne before plunging back into the mire. In anticipation for a German charge, Barry details the melee weapons dispersed amongst the terrified soldiers:

Captain Sheridan came up cursing from his dugout with Christy Moran, looking like storybook monsters. But they all looked like storybook monsters. The sergeant carried a canvas bag of trench weapons, more like the weapons of medieval times than anything else, sticks with nails in them, rough-cast things with iron knobs, and he was handing these out. Willie was given a thing like an Indian tomahawk, and he stuffed it into his webbing [109]

As is noted here, and throughout the novel, Barry’s references to ancient skirmishes squarely conveys the violence of trench warfare. Of the instance excerpted, Barry’s initial analogy of Sheridan and Moran resembling ‘storybook monsters’ is, in equal measure, comical and horrifying: being at once akin to a childhood memory of such tales and also strikingly frightening, with the gas-masks giving each man an otherworldly countenance. Succeeding this, Barry then details the weapons handed out by the two men. With such analogical comparisons to ‘storybook monsters’, the war is often of a liminal standing between fable and reality, with Barry’s prose treading this line frequently. Often, however, the fable dissipates to a haunting reality: the subjective interpretation of the appearance of ‘the weapons of medieval times’ being then drawn to the precise detail of Dunne’s gift being ‘like an Indian tomahawk’ beautifully shows this process; an impressionistic image is established and is then removed for a more obvious, exact comparison. By coupling the distorted miens of the soldier with their melee weapons of the ‘medieval’ age, Barry is not only drawing a parallel with ancient epic tales of battle, but also the brutality of such stories: the makeshift quality of these weapons, note the repetition of the non-descript noun, ‘thing’, such was the improvised and shoddy quality of them, establishes the savagery of the scene. The initial contrast to the ‘storybook monsters’ is now, by the presence of the weapons, no longer a mythical sight, but rather a starkly real depiction of the soldiers preparing to defend themselves. Again, the coalescence of the past and the present portrays the reality of the war, by way of association to known stories of a bygone, or even fabled, age.

The storyteller quality to A Long Long Way is characteristic of Barry’s literature. At times, A Long Long Way reads as an account, one passed from, or inherited by, speaker to listener, as is archetypal of Barry’s prose. Barry’s writing, both preceding and succeeding the novel, retains a storyteller voice being often narrated from an unbroken first-person telling, unbroken in the sense that the narrative remains linked to the single perspective of the novel’s protagonist. Within A Long Long Way, however, the ‘eyewitness account’[2] of Days Without End, for instance, is still evident: the narrator, while not present as a member of or alongside the men of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, remains moored either to Dunne or, intermittently, his fellow soldiers:

The storyteller quality to A Long Long Way is characteristic of Barry’s literature. At times, A Long Long Way reads as an account, one passed from, or inherited by, speaker to listener, as is archetypal of Barry’s prose. Barry’s writing, both preceding and succeeding the novel, retains a storyteller voice being often narrated from an unbroken first-person telling, unbroken in the sense that the narrative remains linked to the single perspective of the novel’s protagonist. Within A Long Long Way, however, the ‘eyewitness account’[2] of Days Without End, for instance, is still evident: the narrator, while not present as a member of or alongside the men of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers, remains moored either to Dunne or, intermittently, his fellow soldiers:

What was remarkable was the strange yellow-tinged cloud that had just appeared from nowhere like a sea fog. But not like a fog really, he knew what a flaming fog looked like, for God’s sake, being born and bred near the sea in fucking Kingstown. He watched for a few seconds in his mirror, straining to see and straining to understand. It was about four o’clock, and all as peaceful as anything. Not even the guns were firing now. The caterpillars foamed on the yellow flowers [43]

Here, Barry narrates the scene from the perspective of Christy Moran, the regiment’s caustic sergeant-major. Indeed, while Barry’s voice is typically tethered to Dunne, remaining anchored to the Private throughout, in such fleeting instances of omniscience, as excerpted, Barry breaks ties with Dunne; by doing so, Barry is not restrained to the single limited, subjective stand-point of Dunne, and so may narrate the inner-thoughts of the Private’s fellow-soldiers. It is during such points that Barry’s narrator, or persona, is most evidently a storyteller, as though the narrative is almost an informal, conversational monologue between the speaker and the reader. With the regiment’s first experience of warfare, the comparison between the encroaching mustard-gas and ‘a sea fog’ is then retracted by Barry, as though the simile was inadequate in its detailing of the ‘cloud’. The analogy’s initial use, to delineate the murkiness of the approaching gas, then leads, momentarily, to a bifurcation of the scene, transitioning focus to Moran’s origins, his place of birth within Kingstown. Further to this, in the moment of the writer’s doubt, the narrator’s self-chastisement mimics Moran’s typical offhand rebukes, as though the narrator, through Moran, is effectively mocking the drawn comparison: of course Moran knows what ‘fog’ looks like, being ‘bred near the sea in fucking Kingstown’, and what he is facing is not that. Both the narrator and Moran know the appearance of ‘sea fog’, but what is advancing upon Moran is a new sight to the Irishman entirely. The effect of this shift to Moran is one which establishes the narrator as something of raconteur, narrating a telling of the story to the reader. In truth, the persona of the narrator mimics discourse, being even conversational at times, and yet still does not detract from the reality of the narrative, but, rather conversely, conveys a more personal telling: the subjectivity of these men remains evident, even if, occasionally, there is something of a communal perspective from several soldiers being given.

By untethering the narrative from the thoughts of Private Dunne to that of the soldiers surrounding him, Barry has created one of his finest portrayals: Dunne’s sergeant-major, the truculent Christy Moran, a fierce soldier, from a line of such men, whose dedication to his company is matched only by his contempt for the flag he serves. Indeed, A Long Long Way’s primary focus is upon how war forever changes Dunne, from the naïve and meek son of a policeman to a stateless ghost drifting through an endless war, the novel also branches out to highlight the ramifications of war upon others. With Christy Moran, his experience during the war breaks the sergeant-major’s stoicism to reveal a man completely trusting of those alongside himself. ‘With the face of an eagle’ (22) and an equally threatening foul-mouth, to the men of his company, Moran is often believed to be a belligerent leader, but one even-handed and peaceable with those under his charge. Beneath his hardened carapace, however, there is a man wracked by guilt. Like Dunne, Moran, too, is haunted by his family, specifically, his belief that he has failed his wife, coming out to war after her maiming in an accident. But while Dunne searches for domesticity, Moran has taken flight from the homestead. Within Chapter Ten, Barry discloses the ‘inward thinking’ (130) of the 16th Division; their silent musings are forefronted as the narrator, unbound from Dunne, delineates Moran’s shame. Barry lingers upon the sergeant-major’s desire to ‘come down away from what he was to the men’ (131) in order to speak candidly and to sing alongside the soldiers of his Division. In this single moment, Moran’s acerbic commentary is shown to be nothing more than shield by which he may hide behind, fearful of the men finding his wife’s accident to be comical, if revealed:

By untethering the narrative from the thoughts of Private Dunne to that of the soldiers surrounding him, Barry has created one of his finest portrayals: Dunne’s sergeant-major, the truculent Christy Moran, a fierce soldier, from a line of such men, whose dedication to his company is matched only by his contempt for the flag he serves. Indeed, A Long Long Way’s primary focus is upon how war forever changes Dunne, from the naïve and meek son of a policeman to a stateless ghost drifting through an endless war, the novel also branches out to highlight the ramifications of war upon others. With Christy Moran, his experience during the war breaks the sergeant-major’s stoicism to reveal a man completely trusting of those alongside himself. ‘With the face of an eagle’ (22) and an equally threatening foul-mouth, to the men of his company, Moran is often believed to be a belligerent leader, but one even-handed and peaceable with those under his charge. Beneath his hardened carapace, however, there is a man wracked by guilt. Like Dunne, Moran, too, is haunted by his family, specifically, his belief that he has failed his wife, coming out to war after her maiming in an accident. But while Dunne searches for domesticity, Moran has taken flight from the homestead. Within Chapter Ten, Barry discloses the ‘inward thinking’ (130) of the 16th Division; their silent musings are forefronted as the narrator, unbound from Dunne, delineates Moran’s shame. Barry lingers upon the sergeant-major’s desire to ‘come down away from what he was to the men’ (131) in order to speak candidly and to sing alongside the soldiers of his Division. In this single moment, Moran’s acerbic commentary is shown to be nothing more than shield by which he may hide behind, fearful of the men finding his wife’s accident to be comical, if revealed:

He wanted them to stand in place of his listening wife, with her sharp features and her ruined hand, lost in a miserable accident in their house. He wanted to tell them about his wife, obscurely desiring to, desiring, but terrified they might laugh at him, worse, laugh at her, for what had befallen her, a laughter that would be worse to him than bullets [130-131]

The saddening echo of his ‘want’ and ‘desire’ conveys the restraint of a man defined for his verbosity. It is a private longing which distils the true fear of a seemingly fearless soldier; it is also a disclosure that Barry, while establishing the sergeant-major’s hidden motivation for coming to war, — even begrudgingly serving within the King’s army due to his inability to remain with his wife — also notes Moran’s ‘love’ for his soldiers. When Moran comes to reveal the accident, seven chapters later, it is done in complete faith with his men, and is a baring which, due to the men’s compassion, unearths a cherished and longed for boon for Moran:

A strange flood of relief washed over Christy Moran’s thinking head. He didn’t know why hardly. It was ridiculous to feel relief with such a ruckus around them […] A person might have thought that Christy Moran would have then proceeded to tell the men how he felt about them., since that maybe had been the point of the story. But such was his sense of victory, it overwhelmed him, he said no more, he forgot to say what had long hidden in his mind. But it hardly mattered, in essence, they knew well his mind. They knew it well, without him having to say a word [219]

Here, Barry, having intermittently conveyed the ‘inward thinking’ (130) of Moran throughout the novel, presents the highest victory for the sergeant-major in his ‘thinking’ finally being voiced: subsequently, his men understand his turmoil. Barry’s omniscient narrator details the ‘relief’ felt by Moran in trusting his men with his great shame. ‘The flood’ is no longer contained by a repressed silence, but rather becomes a form of rejuvenation, a cleansing of his mind, his ‘thinking head’. There is no ‘point’, per se, to Moran’s memory other than to show a man coming to terms with his guilt; it is, in essence, a confession. Within this moment, the longing desire he once felt to speak openly is alleviated and the men understand their leader without him having to ‘say a word’. Uncharacteristically to the men, Moran is stilled by their reaction. Through his confession, Moran’s flight from home is halted as, with the confidence of his men, he has found a form of family within the Division. In his shame, he has found a form of home.

Like his sergeant-major, Dunne forges a new family with the Division, having, by his final furlough back to Wicklow, lost not only his understanding of Ireland, but also his ties with his own family. By the October of 1918, William Dunne is far removed from the once impressionable apprentice who volunteered in order to surpass the pencilled lines of a door-frame. While the novel’s narrator initially drew analogical parallels between the war within Europe and the epic tales of literature, by the denouement of the novel no such epicism are made; instead, Dunne, himself, is frequently compared to a spectre, a ‘ghost’ (252) without an understanding of his world:

He stood there for a while. He felt like a ghost, a person returned from some dark regions, no longer a human person. He felt like just the wisps and scraps of a person [252]

Through war, Dunne has been hollowed of his being, left as little more than a shell, unable to piece himself together. Having lost his father’s respect for his sympathy with the Irish nationalists, Gretta, his girlfriend, for his indiscretion with a prostitute, his own country, in his confusion over the conflicted attitudes towards Home Rule, and his own identity, being equally derided for his service to the British army by the Irish as he is deemed a traitor and untrustworthy by the British, due to the growing malaise of contempt towards the army back within Ireland. His hope of a life after the war is dashed by these losses. In truth, by the age of twenty-one, the front-line is Dunne’s only home:

He was twenty-one now. That was a grown man, right enough. He couldn’t cross back quick enough. It was very strange to him. All the ‘valleys of death’ he had been through, all the fields of dead men, all the insane noise, and wastage of living heart, you would think would have deterred him mightily. He didn’t understand the war in the upshot, and he had thought to himself a dozen times and more that no one on earth understood it rightly. And he certainly didn’t desire it and he feared it like the hunted animal fears the hunter and the hounds — but all the same he grew happier the closer he drew to his friends [282]

The true tragedy of A Long Long Way is that, by the end of Dunne’s service, the political and social upheaval of Ireland has forever altered the country to the point that Dunne knows no home. Indeed, while the title is excerpted from the marching song ‘It’s a Long Way to Tipperary’ (1912), Dunne’s ‘heart’ is not in search of Ireland, but rather of his family at the front. Divested of his origin, Dunne is simply a soldier without a purpose or a cause. As may the dirt that buries him, Dunne is ‘swept away’ by the war. His meagre belongings, his ‘uniform and other effects, his soldier’s small-book, a volume of Dostoevsky, and a small porcelain horse’ (291), were all collected during his service and all which may evidence his existence. The stories behind the personal possessions of the single ‘volume of Dostoevsky, and a small porcelain horse’ are to be forever unknown to his kin. Through Dunne, Barry has created a character who is not only defined by war, but subsumed by and lost to it.

[1] John Milton, Paradise Lost (London: Penguin Classics, 2003), p. 42

“Soldering”??? Do you mean “soldiering”?

LikeLike

Thanks. Correction made.

LikeLike