Of the Coen brothers’ oeuvre, their work characteristically contains an eclectic diversity of raconteurs, wastrels, itinerants, killers, pragmatists and nincompoops, to name just a few typical attributes. Indeed, with the agendas and objectives of these protagonists varying dramatically, to succinctly summarise a single defining attribute of a Coen brothers’ character is to negate the complexity of their work. Multiple lists, usually headed with the superlative adjectives ‘best’, ‘greatest’, or ‘definitive’, have been compiled from characters from throughout their filmography, with the like of the dauntless Marge Gunderson (Frances McDormand), the slothful Jeffery “The Dude” Lebowski (Jeff Bridges), and the indomitable Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem) claiming the title. Rather than focus upon such a list, this series of articles will instead explore how several selected characters are both akin to and unique from the other characters of the brothers’ filmography. This is not to be a ranked series, so to speak, but rather a look at the attributes of five characters who have been unfairly mantled from the light in the wake of the Coens’ ‘greatest’ creations. For the first, the judicious gangster Tom Reagan (Gabriel Byrne), trusted advisor to Irish-American crime lord Liam “Leo” O’Bannon (Albert Finney), is studied, looking specifically at how his machinations and scheming is both entwinned with and uniquely specific from the protagonists preceding and succeeding Miller’s Crossing (1990).

From the outset, Reagan’s advisory commitment to O’Bannon occupies a liminal standing between patriarchal adherence and fraternal partnership; the first scene of Miller’s Crossing is one of negotiation, of council between two mobsters and their deferential lieutenants. As O’Bannon indifferently listens to the garrulous, hot-headed Johnny Casper’s (Jon Polito) musings upon the importance of ethics to ‘fixing’ boxing matches, Reagan, shadowed to the right-hand of his premier, no less, silently listens. Ultimately, Casper’s request to kill Bernie Bernbaum (John Turturro), a ‘small-time’ grifter selling Casper’s ‘fix’ to the highest bidder, is offhandedly dismissed by O’Bannon, the taciturn Reagan, ‘peering over his drink’, foresees the inevitable fallout from Casper’s humiliation. Once Casper and his ‘flunky’ Eddie “The Dane” Dane (J.E. Freeman) clear out, the Coens perfectly convey Reagan’s adroit perception: with the ebullient O’Bannon, smirking at his belittling of the ‘schnook’ Caspar, in his first utterance, having moved away from his liege, Reagan, in a characteristically clipped, laconic declaration, simply posits the simple read, ‘bad play, Leo’. It is a declaration which anticipates the livid Caspar’s volatile response. In a precautionary plea to his naively buoyant, even conceited, master to ‘think about what protecting Bernie gets us. Think about what offending Caspar loses us’ Reagan’s pragmatism, his objectivity is evident. While O’Bannon opines his disdain for thinking, and in-turn rational thought, Reagan’s benevolent riposte cuts to the heart of O’Bannon’s oversight, as he simply observes, ‘yeah, well, think about whether you should start’. The repetition of the stative verb ‘think’ encapsulates Reagan’s defining attribute, and his desire to impress upon O’Bannon the ‘smart play’. Indeed, his ability to ‘think’, to plot his and O’Bannon’s stratagem, when coupled with his faculty of persuasion, is Reagan’s defining quality. It is, after all, what has kept O’Bannon as a dominant force within the criminal underworld and political spheres of prohibition. However, despite O’Bannon failing to heed Reagan’s advice, plunging himself and Casper into a desperate power-struggle, the Coens nevertheless establish a familial kinship between the two men. Although O’Bannon desires to ‘square’ Reagan’s gambling debts with the unseen, yet ubiquitous, presence of the bookkeeper Lazarre, the latter, in his advisory position, thinks for his leader in order to keep his power-hold secure. However, beneath their affectionate kinship, lies a uniting individual: the acerbic, calculated Verna Bernbaum (Marcia Gay-Harden).

Indeed, while forewarning the besotted O’Bannon to leave Verna, despite having his own furtive affair with her, Reagan labels the Bernbaum family as tricksters, with the brother and sister duo equally committed to ‘the angle’: for Verna, in her bid to protect her brother, Bernie, O’Bannon is her mark. To the romantic O’Bannon, his judgement love-addled and askew, Reagan is being sullen, a ‘prickly pear’, who shouldn’t ‘run down’ Verna simply for caring about her brother. Reagan, in his objectivity, believes that ‘friendship’s got nothing to do with it’ when it comes to Verna. In his objectivity, Reagan is able to share a bed with Verna and then council O’Bannon to ‘dump’ her within the same night, as both briefly occupy the adjoining rooms of Reagan’s sparse apartment. In his read of Verna, Reagan sees her arrangement with O’Bannon as a ‘play’, a ‘grift’. Reagan’s own clandestine relationship with her, in essence, exposes this. However, beyond a read of the other, it remains ambiguous as to what either gets from their surreptitious affair. There is a detached taciturnity to the pair’s exchanges: neither profess to love the other, but, in their deceit and betrayal of O’Bannon, they have a shared aptitude for the ‘smart play’, an attribute foreign to the forlorn O’Bannon. While Verna angles for her brother, the ramifications lead to an all-out war: O’Bannon will not sanction the death of his love’s only family; to Reagan’s pragmatic perspective, ‘you do things for a reason’: going ‘to the mat’ for some wastrel bookie against an embolden enemy is not ‘the smart play’. To Reagan and Verna, caution, regardless of the cost, is paramount.

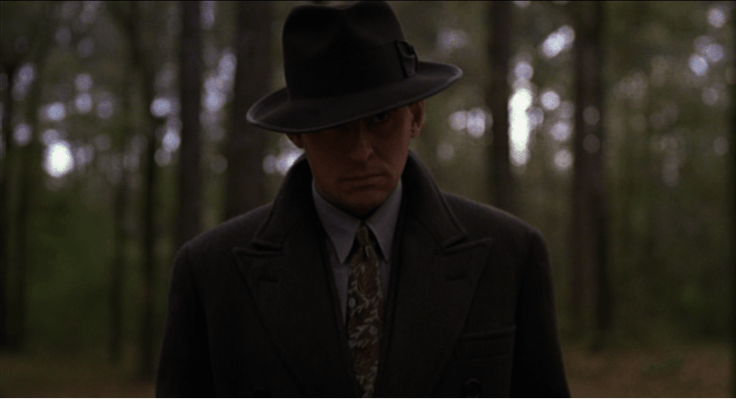

In response to O’Bannon’s obstinance, Reagan must initiate his own intricate ‘smart play’: confessing to his affair with Verna, Reagan is cast out by O’Bannon and exiled from the organisation; now, as a free agent, Reagan ‘plays’ both sides, shoring up his position as a confidant of Caspar while also keeping his erstwhile master’s interests at heart. Now, under the threat of death if caught, Reagan’s determination, his ability as a strategist, as an intrigant, is beautifully portrayed. Here, the Coens and their cinematographer Barry Sonnenfeld tether the audience to the itinerant Reagan. Upon only two occasions are we not anchored to Reagan: the first, during O’Bannon’s eloquent foiling of an assassination attempt, and the second, during the Casper-aligned police force’s merciless assault upon the Sons of Erin Social Club. For the rest of narrative, Reagan is our linchpin. Throughout, their penchant for wide-angled lenses set intimately close to their subject[1], typically from within the middle of a conversation, traps Reagan within each exchange. Within each exchange, there is a palpable sense of peril, as he navigates each negotiation, from the searching Dane to the volatile and unpredictable Bernie Bernbaum. The use of singles, of shot reverse shot, heightens Reagan’s play: Miller’s Crossing, beyond its dialectic wordplay and spear-sharp ripostes, is a film of reactions, of reading and discerning the miens of those listening to Reagan’s deceptions. Further to this, the Coens and Sonnenfeld’s inclusion of the ‘push-in’, gradually reduces the scale of Reagan’s surroundings, his environment steadily closing in upon him.

It’s a simple addition, and not one typical of the Coens’ work, but it encapsulates the pressure and threat shouldered, somewhat, selflessly by the plotting Reagan. Finally, with the principle motifs of betrayal and double-crossing serving as a through-line within each of Reagan’s meetings, scenes are often mirrored; take for instance, Reagan’s first private meeting with Casper and Dane. Sat facing Casper with Dane, the latter lounging within earshot over Reagan’s right shoulder, the meeting concludes with Reagan beaten by submissive henchmen Tic-Tac (Al Mancini) and Frankie (Mike Starr), a mismatched little and large paring, respectively; later on, with the same staging as their disastrous exchange, Reagan, seemingly siding with Casper, proves his worth: revealing the location of Bernie Bernbaum, hiding at the Royale Hotel. This symmetry adroitly conveys the repetitive and cyclical nature of the ‘plays’ of these schemers. Of how these people, determined in their resolve, constantly face each other under varying circumstances. So fickle are the bonds which unite these disparate collectives, that even though a first meeting may end in bloodshed, the second may conclude with a vow of loyalty. Typically, the mirroring of such conferences establishes Reagan’s skill as a strategist, how his invaluable council is sort after, despite maligning Casper’s first attempt to recruit him. Of all of the Coens’ protagonist, Reagan is arguably the most present perspective: while attention is given to those he is manipulating, the Coens’ central focus is always upon the toll and burden borne by Reagan in enacting his own scheme. With all of his machinations, Reagan is forever our subject.

Although not the most loquacious protagonist, Reagan’s language is poetically sardonic and derisive, openly critiquing and objectively assessing those around him. With Miller’s Crossing heavily indebted to Dashiell Hammett’s work, owing particularly to Hammett’s debut novel Red Harvest (1929) in its depiction of a volatile gang-war and the author’s fourth novel, The Glass Key (1931), through the comradeship between gambler Ned Beaumont and crime-lord Paul Madvig, the language of Hammett’s work is evidenced throughout Reagan’s conversations. Further to this, the characters’ penchants for neologisms embed the neo-noir malaise of its influences: a ‘twist’, used more as a derogatory conversion from the verb, is in reference to a woman; to ‘dangle’ is to leave; while a ‘play’ refers to a course of action, or scheme; further to this, idioms such as showing someone the ‘high-hat’, enquiring upon the ‘rumpus’, and labelling someone as a ‘straight shooter’ or ‘a square gee’ all convey the dialectic variations of these characters’ vernacular. In addition to these locutions, the use of dated colloquialisms, ‘schnook’ for a fool or a ‘stiff’ for a corpse, and racial slurs ‘dago’, ‘eyeties’, ‘guinea’, ‘sheeny’, and ‘yid’ all evidences the varying ethnicities of the warring tribes of the narrative, and the amalgamation of the varying dialects to formulate the localisms of the unnamed east coast city. Often, inferring the meanings of such irregular or outdated phraseologies is a gradual process, but the entwinned cadences of these speakers formulates a uniquely stylistic and yet natural sounding dialogue. With the Coens’ characteristically attuned ear for speech, the prose of Miller’s Crossing is one of which flawlessly embodies the natures of its speakers.

However, of all of the pawns in play, it is Reagan, nonetheless, with his mellifluous Dublin-intonation, who’s taciturn articulations dictate the actions of others. With his clipped, discreet interjections, Reagan often manipulates and manoeuvres others into a position of his devising. However, his schemes are not flawless, and it is this simple truth which creates the desperation within Tom Reagan’s lapidary nature. In addition to his prowess as an aide-de-camp to O’Bannon, Reagan’s objectivity is often maligned as being heartless. In direct contrast to his master, a self-proclaimed ‘big-hearted slob’, Reagan does not permit such romantic notions: not only does he reject the multiple offers from both waring leaders to cover his debts, but Reagan, as a ‘point of pride’, keeps friendship and love at a distance. Only at one point, in his sparing of the pitiable Bernie Bernbaum after he pleads with Reagan to ‘look into’ his heart, does he permit himself compassion; it is an act which will disrupt his scheme to his own detriment. Indeed, the crafted mirroring, the sagacious dialogue and the brinkmanship of these grifters coalesces into a single scene. Often, Reagan’s hinterland death-march of a pleading Bernie Bernbaum is typically cited as the iconic moment of the film, but it is what follows, the ramifications of his merciful decision within the woodland, which truly shows the taut power of Miller’s Crossing.

Reagan’s scheme to protect O’Bannon is hinged upon the fate of one person: the duplicitous Bernie Bernbaum. During his introduction, meeting Reagan after breaking into his apartment, Bernbaum is ebullient and exuberant while elucidating a prospective scam, the same sort of ‘fix’ which has led to a bounty being placed upon him. Entering his apartment, Reagan takes a seat and answers the insistently roaring dial telephone, dismissing the caller’s calls for repayment, before then looking across to address his uninvited guest. Bernbaum sits opposite him, slouched and lounging within the depths of the armchair. Here, with his pallid complexion, Bernbaum appears vampiric, threatening despite his wide smile, broader than the short brim of his bowler hat. Here, Bernbaum attempts to lure Reagan into a gamble, a confederacy between friends, citing his motto that ‘a guy can’t have too many’. It is a grift, and of the same sort which Reagan warned O’Bannon about: the assertion of the Bernbaums and their ‘grifter’ kind gaining credence. However, when the two meet again, with Bernbaum now enshrouded within shadows and sat within Reagan’s chair, their exchange is centred upon Bernbaum’s powerplay. The excerpt is taken from the original script, but has been edited to the film’s version.

The windows throw moonlit squares onto the floor. We can see only the legs of someone sitting in the armchair.

Tom: ‘Lo, Bernie. Come on in, make yourself at home.

Bernie turns on the lamn on the table at his elbow. He holds a gun casually in his lap.

Bernie: ‘Lo, Tom. Thought I’d do that, since you didn’t seem to be in. Figured it was a bad idea to wait in the hall, seeing as I’m supposed to be dead.

Tom: Mm.

Bernie: How’d you know it was me?

Tom: You’re the only person I know’d knock and break in.

Bernie: Your other friends wouldn’t break in, huh?

Tom shakes his head.

Tom: My other friends wanna kill me, so they wouldn’t knock.

He crosses to the chair facing Bernie’s.

. . . What’s on your mind, Bernie?

Bernie: Things. . . I guess you must be kind of angry. I’m supposed to be gone, far away. I guess it seems sort of irresponsible, my being here. . .

Bernie leaves room for a response but Tom is only listening.

. . . And I was gonna leave. Honest I was. But then I started thinking. If I stuck around, that would not be good for you. And then I started thinking that. . . that might not be bad for me.

Tom still doesn’t answer.

. . . I guess you didn’t see the play you gave me. I mean what’m I gonna do? If I leave, I got nothing–no money, no friends, nothing. If I stay, I got you. Anyone finds out I’m alive– you’re dead, so. . . I got you, Tommy.

Tom is silent.

. . . What’s the matter, you got nothin’ to crack wise about? Bernie ain’t so funny anymore?

Bernie’s lip is quivering. His voice is softer:

. . . I guess I made kinda a fool a myself out there. . . balling away like a twist. I guess… I guess I turned yellow…you didn’t tell anyone about that.

Tom: No.

Bernie: Course you know about it. . . its . . . It’s a painful memory. And I can’t help remembering that you put the finger on me, and you took me out there to whack me. . . I know you didn’t… I know you didn’t shoot me. . . but. . . but–

Tom: But what have I done for you lately?

Bernie: Don’t smart me.

He stares hard at Tom for a moment.

. . . See, I wanna watch you squirm. I wanna see you sweat a little. And when you smart me, it ruins it.

Bernie gets to his feet, keeping the gun trained on Tom.

. . . There’s one other thing I want. I wanna see Johnny Caspar cold and stiff. That’s what you’ll do for your friend Bernie. . .

He has opened the door to the flat.

. . . In the meantime I’ll stay outa sight. But if Caspar ain’t stiff in a couple of days I start eating in restaurants.

The door shuts behind him.

Tom, heretofore very still, springs from the chair, goes to the bedroom and re-emerges with a gun. Tom runs across to the open window and clambers out. He hangs by his hands for one brief moment and then drops.

THE ALLEY

As his bare feet hit the pavement. Tom is a silhouette in the lamplight from the end of the alley. He straightens from his crouch and runs.

BACK DOOR

Of his apartment building–over Tom’s shoulder as he enters frame. The empty, brightly lit hall inside runs straight the length of the building to the front door, which is just closing.

Tom throws open the back door.

HALLWAY

As Tom runs through toward the front. Before reaching the door, he falls violently forward. His gun skates away from him across the floor. He starts to roll over to look behind him and a crunching blow catches him on the chin, snapping his head the rest of the way around and sending him flat onto his back. Bernie, who has emerged from under the staircase, towers over him.

Bernie: You make me laugh, Tommy. You’re gonna catch cold, then you’re no good to me. . . What were you gonna do if you caught me, I’d just squirt a few and then you’d let me go again.

Tom, white-faced and shivering, pulls himself up to sit leaning against the wall.

What is telling, here, is Reagan’s silence: having acquiesced to the ‘balling’ Bernbaum out within the woods, he is seeing a grift which could derail his own scheme. In plotting the safety of O’Bannon, Reagan’s scheme is to remove the threat of the indomitable Dane: by contacting a known associate of Bernbaum and lover of Dane, Mink Larouie (Steve Buscemi), Reagan’s plan is to convince Caspar that the Dane ‘put [Mink] up to’ the fix. In essence, he schemes to rive Caspar from his ‘shadow’, weakening the former as a consequence. Bernbaum’s counter altogether jeopardises this, with Reagan himself now under threat of exposure as a double. Within the exchange, the Coens play two grifters against each other, and yet, despite the loquacious Bernbaum, Reagan is stilled and silent, with ‘nothing to crack wise about’. He simply listens, interjecting only to indignantly rage — barking ‘but what have I done for you lately?’ at Bernbaum’s betrayal. As a consequence of his ‘heart’, Reagan has now lost the ‘smart play’, and at the mercy of the man he once granted clemency. Indeed, the compassion he exhibited is not permitted within his world of grifts and schemes. Rather, his stoic nature, his ‘Machiavellian traits’[2] as noted by Byrne, are necessary, if precautionary, attributes needed for his work.

Despite his hopelessness as a gambler, Lazarre never does see the ‘five-hundred’ he is owed, the ‘luck’ Reagan desperately needs is never forthcoming. Instead, he must rely solely upon his skill as an opportunist and his skill as an orator. The irony of an opportunist having no luck evidences the sheer scale of Reagan’s machinations: throughout, there is absolutely no certainty that his plot of betrayal and deception will work. It is the ‘smart play’, but a ‘play’ that is undertaken out of desperation and exasperation upon the behalf of an unknowing and sentimental romantic. Indeed, while much has been made of Reagan’s fedora, of his dream of his hat blowing away down an avenue of trees, Reagan is too practical, too rational, and ‘objective’[3] to entertain Verna’s attempt to elucidate meaning from the abstract. In place of the hat drifting listlessly, O’Bannon strides off after Verna and away from the only friend he needs.

Reagan, ever the pragmatist, having saved O’Bannon and his empire, strikes out alone, refusing the desperate pleas of his liege to return to the fold. For the first time, his aquiline aspect is not bruised behind a flurry of punches, nor is his lip freshly split. He no longer bares the scars of his play. In synchronicity, the pair, separated, don their fedoras. It seems, even though that Reagan has now untethered himself from a life of scheming, he will forever remain entwinned with his master. Now, and unlike in his dream, his hat remains fast to him. He raises his head: statley and dignified. To Tom Reagan after all, there is ‘nothing more foolish than a man chasing his hat’. As he watches O’Bannon pursue the grieving Verna, Reagan remains anchored, chasing neither his hat nor his friend. Now, he serves no one: the smartest play of all.

[1] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5UE3jz_O_EM (This video was a cornerstone in the discussion upon the camerawork of the film)

Leave a comment